Illustration: solvejg_art for OVD-Info

“The government’s way or the highway”: how Russian authorities persecute teachers with an anti-war stance

The original report was published on 2 September 2024.

Executive Summary

Since the beginning of 2022, the Russian education sector has been undergoing significant changes. The authorities intensified their focus on patriotic education and started requiring teachers to actively support the war. Some education workers have quit or left the country due to new working conditions, pressure, and fear of mobilisation. This became one of the factors leading to the shortage of staff.

Those who stayed found it difficult to express their political views openly. They had to compromise in their teaching methods and use Aesopian language in their work.

Teachers experience heavy pressure not only from their management, but also in the form of administrative and even criminal prosecution. In some cases, this pressure is preceded by denunciations, often written by students and their parents.

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the year 2022 marked the highest number of administrative cases against teachers for their anti-war stance, with a total of 71 cases. In addition, 23 criminal cases have been opened since the war began, mostly for speaking out about the war. However, there was a downward trend in the number of such cases in 2023 and 2024.

In 2023, the number of cases for cyberbullying against teachers by pro-war activists increased, especially in occupied Crimea: opponents of the war were harassed in local pro-war Telegram channels.

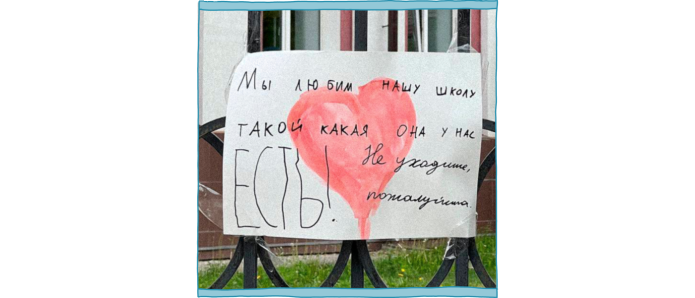

Despite the pressure, some teachers have received support from students and their parents as well as colleagues, and in rare cases they have succeeded in getting their cases dropped or obtaining compensation for unlawful dismissal in court.

The majority of the teachers subjected to pressure were fired (59% of the total number of those persecuted), and some emigrated from Russia (15%). This indicates a significant crackdown on academic freedom in Russia.

Those who have experienced pressure are not always willing to share their story publicly and much less give details. We have conducted 20 interviews. It is worth noting that most of those interviewed were involved in activism prior to their persecution.

Troubled times for the education system and the pressure are having comprehensive consequences for teachers, including causing them to quit the profession. In some cases, forced emigration significantly worsens the teachers’ situation: they have to drastically change their lifestyle and sometimes even their work, for instance, to shift from teaching children to teaching adults, while there is no way back for them to teach in Russia again.

Opening Section

Introduction

In Russia, the year 2023 was declared the Year of Teachers and Mentors. However, in the same year 193,000 teachers — 14% of the total number of teachers in the country — quit schools. The government’s demand for education workers to support the regime is growing, while teachers are becoming increasingly tired of the pressure from above. Meanwhile, the teaching community has been under public and government scrutiny for a long time. Further examples show that teachers are increasingly being held to expectations as role models of morality.

In recent years, there has been a rise in the pressure for allegedly inappropriate teachers’ photos on their personal social network profiles: in Barnaul and Omsk, school teachers were forced to resign because of their pictures in swimsuits. A teacher from St. Petersburg was forced to choose between continuing to work at her school and running a TikTok account. Even further, a mere purchase of underwear prompted a denunciation. Teachers’ personal relationships are also under scrutiny: in Krasnoyarsk, a supplementary education teacher was forced to resign due to accusations of «supporting LGBT sexual perverts».

Teachers were required to keep up with government policy even before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and deviating from it could lead to loss of employment. Participation in rallies could cost a teacher their job, as could involvement in opposition political activism in general. Back in 2020, the Higher School of Economics in Moscow decided not to renew the contracts of employees who disagreed with the regime. There were at least seven such employees. At the same time, the university administration presented mass dismissals as a consequence of forced reorganisation, claiming that the employees’ views had nothing to do with it.

On the one hand, the authorities emphasise the importance of supporting teachers, regularly promising salary increases and even implementing a system against teacher cyberbullying. At the same time, officials, judges and members of law enforcement talk about the special moral character of teachers, making it essentially impossible for them to hold and convey their own views. The situation was further complicated after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine with the introduction of lessons and activities designed to justify the war.

This report examines politically motivated pressure on teachers in the period from 24 February 2022 to 14 July 2024. The term «teacher» is defined broadly here: it includes people working in primary, secondary, specialised secondary, higher and supplementary education.

Aims and Objectives of the Report

Independent journalists and researchers have already published articles about Russian teachers during the war. These were articles about the victims of repression and reviews of changes in the educational system. However, we could not find articles by independent media about the persecution of teachers accused of holding an anti-war stance since the beginning of the invasion.

This report sheds light on repression against a vulnerable group that is under increasing pressure from the state. Further, this report can help inform international bodies about the position of those victimised.

This report aims to analyse the types of politically motivated pressure on teachers in the context of the full-scale war in Ukraine.

Objectives of the report:

- To analyse data from OVD-Info and other independent projects, as well as from courts, law enforcement press releases and pro-government media;

- To interview teachers who have experienced pressure;

- To visualise the data.

Research Questions

- Why has the position of teachers become more vulnerable since the outbreak of the war?

- What tools are used to put pressure on teachers criticising the war?

- Does the extent of repression vary from region to region?

- What are the consequences for teachers who oppose the war?

- What is the impact of reactions from professional associations, colleagues, students and their parents?

- How has the situation affected the teachers themselves?

Structure of the Report

Analysis of Publicly Available Data

This report analyses publicly available data on politically motivated repression against teachers between 24 February 2022 and 14 July 2024 from independent and pro-government media. Many cases of pressure are not made public, so analysing publicly available data cannot give us a full picture but still makes it possible to identify key trends.

Our research includes cases of teachers accused of expressing an anti-war stance, ranging from explicit statements against the war to an accidental display of prohibited symbols. An anti-war stance in this report means various forms of criticism against the actions of the Russian military and state. The research covers administrative and criminal cases.

In addition, this report includes cases of extrajudicial persecution:

- Anonymous threats

- Bullying on the internet

- Police interrogations and inspections

- Detentions without further prosecution

- Dissolution of associations/entities

- Suspension from teaching

- Dismissal/termination of employment

- Damage to property

- «Foreign agent» designations

- Coercion to apologise

- Censorship

One of the criteria for selecting cases for analysis was the non-violent nature of the acts imputed to teachers, so the report excludes data on arson and assaults.

The report uses the phrase «accused of having an anti-war stance». This is due to the fact that we could not confirm anti-war views of all the teachers we interviewed; it is possible that they faced pressure by chance.

Analysis of Teachers’ Interviews

Twenty teachers affected by the pressure participated in our research interviews, some anonymously. The respondents were asked about their work experience, relationships with colleagues, students and administrative staff, as well as about the pressure and its consequences.

Another four people refused to be interviewed due to security concerns. At least three of them were located in Russia at the time of our request.

A Teacher and the War: How Teaching changed after Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

A lot has changed in this new reality: syllabi, textbooks, extracurricular activities, and prospects for international cooperation. All this change has forced teachers to compromise in their ways of interacting with students. Of course, in the past the state controlled the educational sphere as well, but the environment in which teachers live and work nowadays is drastically different.

School Curriculum

On 1 September 2023, the government launched new unified school programmes in Geography, Russian Language, History, Social Studies, Literature, and Safe Living Basics. In the previous years, schools were allowed to develop the topics, content and structure of their classes independently while taking the Federal State Educational Standard (FSES) into account. Unified programs will be launched for all the subjects by 2025. In addition, the standards themselves have also been updated: the Ministry of Education has outlined «clear guidelines in terms of the spiritual and patriotic development of children».

Significant changes have taken place in the History curriculum, adding sections titled «Russia Today», «Special Military Operation (SMO)», «Counteracting the West’s Strategy towards Russia», «Falsification of History», «The Revival of Nazism», «Ukrainian Neo-Nazism», «Confrontation with the West», «Ukraine is a Neo-Nazi State», «New Regions», «Special Military Operation and the Russian Society», and «Russia, a Country of Heroes». Another striking example is the new curriculum for Safe Living Basics which includes a course on basic military training for the first time since the Soviet era.

While previously propaganda used to be mainly present in extracurricular activities, it is now becoming institutionalised in the mandatory school curriculum.

Study Materials

On 21 September 2022, the Ministry of Education approved a list of textbooks for use in schools and secondary vocational schools. When preparing lessons using the internet, teachers are allowed to use information strictly from the federal list of educational internet sources.

School textbooks are also revised. For example, the publishing house «Prosveshchenie» (Enlightenment), a monopolist in the textbook market, is erasing any mentions of Kyiv from history textbook chapters about Kyivan Rus’ and adding chapters about the start of the «special military operation», «the West’s obsession with destabilising the situation inside Russia», «Ukraine as an ultra-nationalist state», and so on.

Excerpts from «Medinsky’s textbook» for Russian History (11th grade):

Falsification of History. The U.S. and the European Union have spent a huge amount of money on preparing a special educational curriculum for teaching history, the so-called «textbooks». Neither effort nor resources were spared to «reboot our brains» (this is their professional term), to convince us of the «inherent aggressiveness and colonial nature» of Russia.

Counteracting the West’s Strategy towards Russia. A destabilisation of the situation within Russia has become the West’s obsession. The first target became the perimeter of its borders. For this purpose, overt Russophobia was sponsored in the former Soviet republics. Then, according to the plan, Russia shall be dragged into a series of conflicts and «colour revolutions», its economy shall be thrown out of balance and the government replaced with a controlled one. The final goal is not particularly covert: to disintegrate Russia and gain control over its resources.

Ukraine, an Ultra-Nationalist State. Nowadays in Ukraine, any dissent is harshly persecuted, the opposition is banned, and everything Russian is declared hostile.

A total destruction of everything that testifies to the common history and culture of the brotherly nations is underway. First, there was «decommunisation» — a complete demolition of monuments associated with the USSR. Then came a large-scale destruction of memorials dedicated to the sacrifice of Soviet soldiers during the Great Patriotic War. Then they began to destroy everything which was in one way or another connected with Russia, including monuments to Alexander Pushkin, Empress Catherine II, Russian writers and poets, musicians and scientists.

Ukrainian Neo-Nazis are explicit about who they consider their forefathers. One of the brigades of the Armed Forces of Ukraine was given the name «Edelweiss». This was the name of the Hitler’s division that «stood out» in the extermination of Jews and punitive operations. The symbols of the «Das Reich», «Dead Head» and «Galicia» SS units, which are banned throughout the world, are widely used in the Ukrainian army and National Guard.

Today, once again, just like during the years of the Nazi occupation, the slogans «Hang the Muscovite» and «Beat Russians» have become widespread in Ukraine. While liberating cities, our soldiers keep finding evidence of mass crimes committed by Ukrainian nationalists who abuse civilians and torture prisoners of war.

«Important Conversations»

A landmark change in the school curriculum was the introduction of Conversations about Important Things (or shortly «Important Conversations») lessons aimed at «strengthening the traditional Russian spiritual and moral values» and «fostering patriotism». Such lessons are organised throughout the school year from the 1st to the 11th grade. Every study week begins with an «Important Conversations» lesson: first, the school assembly is held where the Russian flag is raised to the national anthem; after that, the students go to their classrooms to study the content of «Important Conversations» lessons scheduled for half an hour. The topics of the lessons are established by the Ministry of Education which also creates methodological materials for teachers.

As a general rule, it is the homeroom teachers who bear the responsibility of organising «Important Conversations» lessons. These lessons address such topics as «accepting the idea of active love for the Motherland», «willingness to defend one’s Motherland with arms», including the willingnesss to sacrifice one’s life for the sake of the country and «its happiness».

Extracurricular Activities

Besides core classes, schools are required to conduct patriotic events on the occasion of so-called «days of unified actions» which include public holidays and other events such as the «Day of Russian Cinema». Their aim, in the words of the Ministry of Education, is the very same patriotic development of students and forming a «system of values of contemporary Russia» in their minds. The responsibility for organising these activities is put on teachers.

Additionally, schools actively conduct events that do not affect teachers’ work but impact education in general. A clear example of that is the installation of memorial plaques, «desks of heroes» and «interactive complexes». Memorial plaques in schools are installed in the honour of former students killed in Ukraine. «Desks of heroes», which started emerging in 2018 and contained information about soldiers who died in the Great Patriotic War, Chechnya and Syria, are now also set up with the portraits of the «heroes of the SMO». Moreover, some schools deploy entire «interactive complexes» — touch screens with folders and teaching materials for the «civil and patriotic development and introductory military training» that are designed in the shape of the Katyusha rocket launcher or the Spasskaya Tower of the Kremlin. Besides, former servicemen, mostly those who came back from the frontlines in Ukraine, come to schools to conduct «Classes of Valour» and other events, organise drill lessons, mini-parades and militaristic competitions.

In many cases, pupils were encouraged to take part in collecting financial and material aid for the war front or forced to engage in labour for the benefit of the servicemen and their families — for instance, cleaning snow in the inner yards of residential buildings or making beds in barracks. Students also get involved in weaving camouflage nets for the Russian army and aligned in the Z-letter shape.

Organisation of Work

The changes in the curriculum and extracurricular activities go along with staff changes. The authorities have introduced the position of «principal’s advisor for upbringing and cooperation with children’s community associations» at schools. They report to the principal and principal’s deputy responsible for upbringing and discipline, and are tasked with, in particular, the work of homeroom teachers and coordination of patriotic events. Teacher-oriented methodological events have also begun to acquire a military and patriotic orientation. For instance, the programme of the «Mashuk» youth forum in recent years has been more focused on the «development of supra-professional skills» of teachers and educators and «front-to-back permeated with themes of the Year of the Family in the Russian Federation, helping the servicemen in the special military operation zone, as well as assisting their families», its organisers say.

At the same time, schools are closing international programmes, students can no longer pass international language exams in Russia, and teachers are prohibited from participating in international projects founded by «organisations from unfriendly countries». Due to such isolation, teachers and students no longer exchange experience and the quality of Russian education inevitably begins to lag behind international standards.

Meanwhile, the teacher shortage, which was an issue even before the full-scale invasion, has only worsened. The already existing problem of low salaries has been aggravated by an outflow of teachers, in particular due to mobilisation: some get sent to the frontline, while others flee the country.

A less obvious consequence is the deteriorating school discipline. According to teachers, students are appalled by the imposed lessons and activities, so they trust the school system less.

In order to adapt to the new reality, some teachers are forced to make compromises. They use the mandated materials only partially and try analysing them with students, or choose topics that are far removed from the modern context to help their students develop critical thinking. Some teachers try to shorten the duration of the «Important Conversations» lessons or use their slots to discuss current issues at school. When teachers want to avoid current social and political topics in classroom lessons, they employ Aesopian language and conduct more direct conversations with students face-to-face, away from their classmates.

Changes to the Higher Education System

University programmes are undergoing significant changes as well: compulsory courses now include the Foundations of the Russian State, the History of Russia, the Traditional Religions of Russia, and the Traditional Values of Russia. These courses aim to promote the concepts of Russia’s «special path», «traditional values», and the sacralisation of state authority. Additionally, new military training centres are being established, where «veterans» of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine work.

In June 2022, all Russian universities were excluded from the Bologna Process, which supports a unified educational system comprising bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. A month earlier, Russian officials had announced their intention to leave the Bologna Process, describing it as contributing to a «brain drain» in the country.

A major change is the continuously spreading «toxic» labelling of foreign research and educational organisations as «undesirable». Russian institutions working with such organisations may face repercussions. An example of this is the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Saint Petersburg State University. It collaborated with Bard College in the U.S. that had been declared «undesirable» in 2021. Subsequent inspections led to revisions in the faculty’s curriculum, and by autumn 2023, the faculty had ceased to exist in its original form. A similar situation occurred at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA), where the Faculty of Liberal Arts was disbanded. Although it wasn’t directly affiliated with any undesirable organisation, education there followed the Western «liberal arts» model. In March 2022, the Moscow prosecutor’s office claimed the Liberal Arts programme was «designed to undermine Russia’s traditional values and distort its history». They argued it contravened the Russian Constitution regarding care for children and education, and conflicted with the National Security Strategy, which seeks to strengthen the country’s political stability, among other things.

Universities using Western educational models lose their buildings, become subjected to inspections by state agencies, while their staff is forced to leave their positions and the country. It is reported that at least 270 academics from Moscow and St. Petersburg universities have left Russia since the full-scale invasion. Among them are Anton Ivanov, the director of the Space Centre at the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, and Maria Yudkevich, an economist and the vice-president of the Higher School of Economics (HSE), where she had worked for 24 years. Commenting on her resignation, she said, «HSE, as an organisation, is no longer my university. It no longer shares the mission I believe in.» Many other HSE faculty members have also left the country, including professor Nina Belyaeva, the head of the master’s programme in Political Analysis and Public Policy, and economist Konstantin Sonin, who faces criminal charges for spreading «fakes» about the Russian army. According to Sonin’s estimate, at least 150 people have left HSE and Russia.

Since at least spring 2023, university lectures have been monitored by censors, who ensure that course materials align with the current views of the authorities. Most often it affects history lectures: lecturers are demanded to avoid criticising the authorities, including those from the times of the monarchy, and recommended to present only dry summaries of controversial facts without their analysis.

Forms of Pressure on Teachers

Some teachers do not accept the new working conditions, curricula, or the prohibition against expressing opinions that differ from the official stance. This has led to the adaptation of the old mechanisms, as well as the creation of new ones to pressure dissenting teachers.

This study is based on data from 65 school teachers, 54 university teachers and 10 teachers from professional vocational schools, all of whom faced political pressure between 24 February 2022 and 14 July 2024. The sample also includes 18 teachers teaching programmes of additional education and one preschool teacher.

In analysing the data, three main sources of pressure on teachers were identified

Heads of educational institutions have fired teachers or pressured them to resign «voluntarily». Pro-war activists have mostly harassed teachers publicly, publishing their personal data, urging the authorities to «take notice», and organising collective denunciations. In some cases, anonymous pro-war activists have threatened teachers or damaged their property. Law enforcement officers have opened administrative and criminal cases, conducted interrogations and searches, and in some cases also detained individuals for «talks» and threatened them without pursuing further legal action.

How law enforcers target teachers

Prosecution for Administrative Offences

cases of administrative offences

teachers faced prosecution for administrative offences

Prosecution Directly Related to Professional Activity

Out of 106 administrative offence cases, 20 were directly related to the teachers’ professional activities. At least 16 of these cases were opened following denunciation reports submitted by students, their parents, or colleagues.

In 11 out of these 20 cases, teachers were charged with expressing anti-war views during lessons. These cases involved five school teachers, five university lecturers and one college teacher. Two cases were later dismissed due to the statute of limitations. In the remaining nine cases, teachers were fined, with two fines later overturned and seven upheld.

Five administrative cases were opened against four school teachers and one supplementary education teacher for criticising the war in conversations with students during breaks. All of these cases resulted in fines.

In addition to anti-war statements in private conversations with their students, teachers were charged with other offences related to their professional duties. For example, a history teacher from Krasnoyarsk was fined 30,000 rubles (300 USD) for discussing the territorial status of Crimea and the Donbas in an online chat with students. How law enforcement obtained screenshots of the chat remains unclear.

Sergei Averyanov, a computer science teacher from Moscow, faced administrative liability for allegedly drawing a swastika on a classroom blackboard, accompanied by the phrases «Glory to Ukraine!» and «death to Russian halfwits». In court, Averyanov claimed that students drew the swastika and that he wrote the slogans not to «discredit» the army. Regnum News Agency claimed that Averyanov supports the Russian army and wrote pro-Ukrainian slogans to illustrate inappropriate behaviour, to show students what they «shouldn’t do».

Olga Lakhman, a Russian language teacher at an Orsk (Orenburg Region) technical college, instructed her colleagues to display printouts from the Wikipedia page titled «Russian invasion of Ukraine». According to the court judgement, the text included «statements characterising the actions of the Russian army as criminal, aggressive, etc., through cause-and-effect reasoning; negative assessment of actions of the Russian Armed Forces in Ukraine as indicated by the use of such words as ‘aggression’, ‘invasion’, ‘occupation’, ‘depopulation’, ‘killing’, ‘puppet regime’ in their literal meaning; the text also explained the necessity to counteract the use (functioning) of the Russian Armed Forces». Lakhman claimed in court that she did not intend to discredit the army, stating that she was tasked with preparing study material about the special military operation and had simply copied the Wikipedia page without reading its content.

Many of the teachers charged with making anti-war statements in the course of their classes or when speaking with students during breaks did not later deny that they had been discussing the war with their students. In court, they either pleaded guilty or confirmed that the conversation took place while denying that they had discredited the army. At the same time, at least six teachers denied making anti-war statements and claimed that they were victims of libel. For example, Leonid Simonov, the leader of a children’s orchestra in a supplementary education centre in Moscow, denied the accusations of expressing an anti-war position in his conversations with kids and stated that he supported the Russian army and even donated money to a war fund. Courts found Simonov and the five other teachers guilty regardless.

Prosecution Not Directly Related to Professional Activity

In the administrative cases known to us that are not related to teachers’ professional activity, teachers are most often prosecuted for their anti-war publications on the internet and participation in protest events. Other cases exist, too. For example, a children’s team coach Valery Yakovlev from the village of Onokhoy in Buryatia was tried in court three times for «discrediting» the army (Part 1 of Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) after he tore a Z-shaped sticker from the entrance to the sports school three times.

Cases of administrative offences for statements and actions outside working hours

Sometimes, after an administrative conviction unrelated to their professional activities, teachers were bullied at work. For example, eight out of 12 university lecturers prosecuted for their anti-war position expressed outside their workplaces were later fired. School teachers were fired less often in similar situations: we identified only six dismissals out of 25 such cases.

Articles under Which Teachers Were Prosecuted

In the cases related to teachers’ professional activity, teachers were prosecuted under the article on discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). In most cases, teachers were sentenced to a fine of 30,000 rubles (300 USD) whereas the maximum fine under this article is 50,000 rubles (500 USD). Less frequently, courts imposed fines of 40,000 rubles (400 USD), and e only in occupied Crimea higher fines have been recorded. For example, Andrey Belozerov, a teacher at the Belogorsk technological college, received a fine of 42,000 rubles (420 USD) for turning on a video with the song «Bayraktar» during a break in the presence of students. For this, he also received a 13 days’ arrest under the charge of displaying Nazi symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Said Asanov, a mathematics teacher from the village of Ukromnoye near Simferopol, was sentenced to a fine of 45,000 rubles (450 USD) for his anti-war statements while teaching the «Important Conversations» class.

Alongside administrative «discrediting» (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences), anti-war statements may also be punished under Article 280.3 of the Code of Criminal Offences («repeated discrediting of the army») if the «offender» previously received an administrative conviction for the same acts. It means that expressing an anti-war position in a professional context may lead to a criminal charge if a teacher was previously fined under Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences, no matter whether the administrative prosecution was connected with their educational activity.

As for prosecutions not directly related to educational activity, most of the cases were also filed under the article on discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Additional cases were opened under the articles on violating assembly rules (Article 20.2), displaying extremist symbols (Article 20.3), disobeying police orders (Article 19.3), or disorderly conduct (Article 20.1). All of these charges are often applied in cases of politically motivated prosecution.

The case of Pavel Kolosnitsyn, a historian and former lecturer at Novgorod State University, warrants a separate mention. In February 2023, he was sentenced to a fine under the article on abusing mass media freedom (Article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for posting a comment in which he wrote, «Mobilisation is when people who do not want to die send to death people who do not want to fight.» In this comment, he dwelled on possible Russian military casualties. According to OVD-Info data, this article is rarely used. In similar cases, protocols were more often drawn up under the article on «discrediting» the army or even under the criminal article on «fakes» about the military. Law enforcement officers probably decided not to initiate criminal prosecution. The next year though, the teacher did not get his contract extended.

Why Is the Number of Administrative Cases Falling?

Cases of administrative offences against teachers accused of expressing an anti-war stance

The steady decline in administrative cases against teachers appears to be a part of the general trend: fewer people in Russia are being prosecuted for expressing anti-war views. However, the trends in prosecutions of teachers for expression unrelated to their professional activity and for expression in an educational setting differ. In 2023, the number of cases opened for anti-war expression outside the workplace fell around 70% compared with 2022. Meanwhile, the number of cases for anti-war statements teachers made during teaching remains the same in 2022 and 2023. The number of such cases in a year (ten) is too low to draw far-reaching conclusions. This, however, suggests that teachers may have been willing to resist censorship in their professional activity for longer than they were prepared to engage in activism in their personal time.

Geography of cases

Total number of administrative cases against teachers, distributed by region

Criminal Prosecution

criminal cases against 22 teachers

Cases Directly Related to Teachers’ Professional Activity

Four of the 23 criminal cases analysed are linked with teachers’ professional activity. Three of them have been opened for oral statements teachers made during interactions with students.

Irina Gen, an English language teacher from Penza, received a five years’ suspended sentence under the article on «fakes» about the Russian army motivated by political hatred (paragraph «e» of Part 2 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code) because she expressed her negative attitude to the Russian invasion of Ukraine when speaking to school girls. The same charge (supplemented with paragraph «a», Abusing a position of authority) led to a three-year suspended sentence for Irina Sedelnikova, a lecturer at the Nizhny Novgorod branch of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration. During her seminar, she talked about Ukrainian children who died because of the actions of the Russian army. In June 2024, a criminal case was opened in Protvino, Moscow region, against Natalya Taranushenko, a teacher of Russian language and literature (paragraph «e» of Part 2 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code). In spring 2022, she told her students about the events in Bucha during one of her lessons. Following this, a father of one of her students kept writing denunciation reports against her for two years until he got his way. After the case was opened, Taranushenko left Russia.

The case of Ruzilya Bisheva, a Russian language and literature teacher from Saratov, differs from those described above. She has been charged under the article on «repeated discrediting of the army» (Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code). She was previously convicted of an administrative offense for sending out an anti-war petition in a messenger. The criminal case was opened after she sent an email with a joint letter to the Ministry of Education of the Saratov region calling to abolish the «Important Conversations» classes. Bisheva faces up to five years in prison.

Prosecution Not Directly Related to Teachers’ Professional Activity

Eleven more cases are related to anti-war publications on the internet. In two of them, the defendants had been earlier brought to administrative responsibility under the article on discrediting the army for their educational activity. That is why the police were able to charge them under a criminal article.

The former lecturer at a technical school in occupied Crimea Andrey Belozerov, who had previously received an administrative conviction for playing the song «Bayraktar» during a break, has since been criminally charged for a social media post reading, «The Russian Armed Forces are bombing Ukrainian cities and killing Ukrainian civilians.» At the time the case was initiated, Belozerov was no longer employed at the college, so the new charge of «discrediting» couldn’t be linked with his teaching. Still, it was one of the consequences of his earlier prosecution over the «Bayraktar» incident. Belozerov received a criminal fine of 100,000 rubles (1,000 USD) and a ban from administering websites for two years.

A similar situation happened to Olga Lizunkova, an English teacher from the village of Vorotynets in Nizhny Novgorod region. She taught at the local branch of the Nizhny Novgorod Institute of Transport, Service and Tourism. In autumn 2022, she faced an administrative charge for «discrediting» the army for speaking out against the mobilisation during a lecture, urging students not to go to war. A criminal case was later opened after a video surfaced in which Lizunkova called Putin a war criminal. However, the case was eventually dropped due to investigators’ error: at the time the video was posted, the court judgement on the administrative case had not yet come into effect, which meant she could not be charged with «repeated discrediting».

In addition to prosecuting teachers for anti-war publications, Russian authorities have also brought criminal charges against educators for participating in protests and other activist events in their personal time. For example, in 2022, Olga Nazarenko, a pharmacology lecturer at Ivanovo Medical Academy faced two criminal charges. The first case, under Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code, was opened for repeated violations of assembly rules, related to several pickets with slogans such as «No to War» and «I am a Russian against the war. Putin to the Hague!» The second case was opened under the article on «repeated discrediting» of the army (Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code) for placing leaflets that accused the Russian army of war crimes. In autumn 2023, Nazarenko died after falling from a height under circumstances that remain unclear. In December 2023, both criminal cases were dropped due to her death.

Are the Risks of Criminal Prosecution of Teachers Decreasing?

In 2022, 13 «anti-war» criminal cases were opened against teachers, whereas in 2023, there were just five such cases. However, just in the first half of 2024 alone, four new criminal cases were opened making any conclusions about trends premature. The exact date another case was opened remains unclear (it could be either in 2022 or 2023).

At least three of the five criminal cases opened in 2023 involve actions that took place in 2022. For example, Zakhar Zaripov, a mathematics and IT teacher from Sovetskaya Gavan in Khabarovsk region, was charged with posting an anti-war message on 2 March 2022. Similarly, Natalia Narskaya, a vocal instructor from Lyubertsy, faced charges in April 2023 for posting several anti-war messages on VKontakte in 2022. The video that triggered the criminal case against Olga Lizunkova was also recorded at the end of 2022.

Two of the four criminal cases opened in 2024 are also related to events in 2022. Dmitry Lopatin, a biology teacher from Moscow, was charged with disseminating «fakes» about the Russian army for a two-year-old post about the massacre in Bucha. Natalia Taranushenko from Moscow region is facing charges for discussing the events in Bucha with her students during a lesson in April 2022.

The other two criminal cases opened in 2024 stand out because the individuals involved, Dima Zitser and Tamara Eidelman, are prominent public figures. These high-profile cases aside, a clear trend emerges: criminal charges against teachers are often based on older statements rather than recent actions. This could indicate a growing reluctance among educators to express anti-war views, whether at work or in their personal lives.

Administrative penalties for discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) related to anti-war statements made at work can only be imposed within 90 days of the alleged incident. Criminal charges for «discrediting» the army (Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code) and «fakes» about the army (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code) have a six-year statute of limitations, as these are considered medium severity crimes with potential prison sentences of up to five years in the «lightest» cases. Until 14 March 2023, the statute of limitations for these charges was two years, so teachers are currently not facing the risk of prosecution under Part 1 of Article 280.3 or Part 1 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code for statements they made during the first half of 2022. However, in cases where teachers were prosecuted for expressing their anti-war views to students, the authorities have applied the harsher Part 2 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code. This is based on allegations that the teachers acted «with political, ideological, racial, national, or religious hatred or enmity, or out of hatred towards any social group». Under Part 2 of Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code, the maximum prison sentence is ten years, classifying the offence as a serious felony and extending the statute of limitations to ten years.

In cases involving posts or comments online, the statute of limitations for administrative prosecutions is calculated not from the date of publication but from the day when the material is discovered. This allows law enforcement agencies to potentially pursue charges under the Code of Administrative Offences long after the anti-war content was initially posted.

What punishments are handed out to teachers

Non-Systemic Pressure

Cyberbullying

Pro-war activists have developed targeted strategies to suppress dissent within educational institutions. Their tactics often involve cyberbullying: they publicly criticise teachers and their views and publicly urge others to report them to law enforcement and demand action.

Number of instances of cyberbullying against teachers

Harassment of Educators in Occupied Crimea

Since the start of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine, occupied Crimea has accounted for the highest number, eight, of cyberbullying incidents documented.

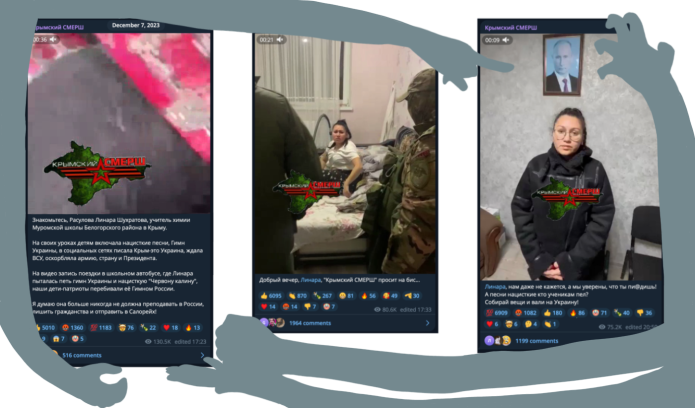

In seven cases of cyberbullying, the harassment was initiated by the Telegram channels «Krymsky SMERSH» («Crimean SMERSH») and «Sevastopol. SMERSH» created by pro-Russian activist Aleksandr Talipov in March 2022 specifically to intimidate people opposing actions of the Russian military. Content posted in these channels often triggers criminal and administrative cases, dismissals and forced public apologies. Videos of arrests, interrogations and apologies are subsequently posted in «Krymsky SMERSH». According to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, there is close cooperation between the channels and law enforcement: pro-war activists supply information to law enforcement, while the authorities reciprocate by sharing footage of arrests.

For instance, after the channel posted a story about a chemistry teacher, Linara Rasulova, who sang the Ukrainian anthem and the song «Chervona Kalina» on a bus, she was detained, and «Krymsky SMERSH» published footage of the arrest. The channel posted a video recording of her apology the same day. According to the channel, she was fired the next day.

Only two of the seven teachers who got in the crosshairs of Talipov’s team avoided making an apology. The rest were forced to record videos of repentance. Even after the apology was published, pro-war activists did not stop harassing them until the teachers were fired. For instance, on 17 April 2023, «Sevastopol. SMERSH» published a video of an apology by Tatyana Odintsova, the head of the audit and accounting department at Sevastopol State University, for her social media profile picture which included a Ukrainian flag. In May, the channel published posts about her children and husband. In June, it announced that Odintsova had been fired.

The only teacher to avoid forced repentance and dismissal after being targeted by“Krymsky SMERSH» was Dmitry Tolstenko, an associate professor at the Crimean Federal University. We couldn’t find the original post about Tolstenko, but based on the publication of «Krym.Realii», he was detained for posting pro-Ukrainian symbols on social networks and sharing videos supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Tolstenko was fined under articles on discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) and displaying extremist symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences).

Bullying of Teachers in the Territory of Russia

In April 2023, «Prikamskie Vityazi» Telegram channel published a post about one of the Perm schools refusing to meet with war veterans as part of the «Important Conversations» lessons. A month later, the channel reported that its administrators visited the school together with local education department officials. They said the school’s deputy principal was «imbued with hatred toward patriotism, for the SMO and the political course of our country». SMERSH activists also accused the school’s management of reprimanding a teacher with pro-Russian views «for her initiative to collect books for children of the Donbas and for her position in general». In an interview with Deutsche Welle, the principal of School No. 12, Elena Rakintseva, said that they have one of the best schools in Russia with a focus on German language studies, that their teaching staff has always valued «a pluralism of opinions, independent decision-making by all participants in the education system and the willingness to take responsibility for them», and that the school «has nurtured an environment free of any pressure for decades». She explained the refusal to allow war veterans to meet with students by the fact that allowing people lacking secondary vocational or higher pedagogical education to teach could harm the children. In August 2023, Rakintseva resigned, followed by 11 other teachers.

Another case in which an entire institution was subjected to bullying occurred in Novosibirsk. The victim of cyberbullying was «Novocollege», whose principal, Sergei Chernyshov, openly opposed the invasion of Ukraine and refused to include the «Important Conversations» course in the curriculum. In spring 2023, a local activist, Dmitry Demin, began publishing posts on his social media page in which he was insulting Chernyshov. The Union of Fathers association, which proclaims its goals to be «the formation of a traditional Russian identity», «spiritual and moral education» and «the promotion of a healthy lifestyle and family values», joined the harassment campaign soon after.

The Novosibirsk-based Union of Fathers association’s online group has more than 2,000 subscribers. In April 2023, it wrote that «the college premises are unfit for classes», that «students smoke indoors» and that «theft is rampant».

However, when interviewed by Novaya Gazeta, the head of the Union of Fathers could neither provide evidence of violations nor name the parents of students who allegedly complained to him. The activities of Dmitry Demin and the Union of Fathers has already caught law enforcement’s attention. In May, representatives of the prosecutor’s office came to the college for an inspection. As a result, they brought three administrative offense charges. «Novocollege» was charged with organising the educational process and carrying out non-profit activities without a special permit and violating anti-terrorist security requirements. Two weeks after the prosecutor’s inspection, Sergei Chernyshov was designated a «foreign agent», resigned and left Russia. That did not stop the pressure though, and the college was fined 50,000 rubles (500 USD) in July 2023. «Novocollege» survived one more academic year, but complex pressure from various sources made the work of the administration and teachers much more complicated. As a result, in April 2024 the college announced its closure.

In the remaining twelve instances, the bullying was directed at specific individuals. In seven of them, dismissal followed. For instance, several teachers from St. Petersburg suffered bullying initiated by the «Podkoverka» Telegram channel. It is a channel about contemporary art, but a significant share of its posts are aimed at insulting cultural figures who hold anti-war views. After one of its posts, three teachers at the Russian State Institute of Performing Arts lost their jobs: Konstantin Uchitel, who was terminated «by mutual agreement», Anastasia Kim and Filipp Vulakh, who left at their own request.

The only known instance outside the occupied territories where a teacher was forced to apologise happened in Sverdlovsk region. «URALLIVE» Telegram channel, affiliated with propagandist Vladimir Solovyov, initiated the bullying campaign. In December 2022, the channel posted a story «exposing» Artem Izgagin, an employee of the Pervouralsk Metallurgical College. The authors pondered what values could instil a teacher who «dressed up in an embroidered shirt, and took pictures with the Ukrainian flag, chanted false ‘For peace’ slogans and called Russian citizens ‘cattle’’’. The next day, State Duma deputy Alexander Khinshtein joined the bullying. A month later, Izgagin was fined 40,000rubles (400 USD) under the article on discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). The URALIVE channel published a video of his apology on the same day.

Anonymous Threats and Property Damage

In autumn 2022, Aleksander Saifullin, a history teacher at Moscow’s College of the Service Sphere No. 10, began receiving anonymous threats. The reason was his open statements against the war during his «Important Conversations» lessons. He kept receiving text messages containing insults, death wishes, and accusations that he was teaching children «all sorts of shit». One of the messages contained Saifullin’s home address. Then a Telegram account with a pro-war symbol on its profile picture sent Saifullin several videos from his lessons in which he could be heard making anti-war statements. Following that, Saifullin left Russia, fearing for his safety.

A primary school teacher at Novgorod’s Eureka high school (name unknown), who used to live in Ukraine, faced threats. In autumn 2022, someone put a note on the street-facing window of her classroom calling her a «Banderite» and advising her to «get out of here».

Cases of property damage have occurred as well. Elena Lazarenko from the Bryansk Professional Pedagogical College said that on the day of her arrest she discovered that someone had drawn a penis on her door. A similar thing happened to Mikhail Lobanov, a politician and lecturer at the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of the Moscow State University, when someone drew the letter Z on his front door in February 2023 and the letter V in June 2023.

Is Non-Systemic Pressure Weakening?

Since July 2023, there have been no reported incidents of non-systemic pressure on teachers apart from cyberbullying. Regarding cyberbullying, 2023 showed a small increase in the number of incidents. In addition, 2023 has seen several cases of online pressure on teacher groups or institutions. In the first half of 2024 though, there were only three documented cases of cyberbullying. Of these, two were in occupied Crimea. The victim in the third case was Alexander Sungurov, a political scientist and professor at the Higher School of Economics, whom Nikita Mikhalkov accused in his programme «Besogon» of involving students in «anti-Russian subversive activities».

Pressure in occupied Crimea and Sevastopol warrants special attention. In 2023, four instances of online bullying of teachers were documented in the region, while in no region in the internationally recognised territory of the Russian Federation have we identified more than two cases per year. Despite the generally small number of cases, it is evident that only Crimea and Sevastopol have systemic working tools engaged in bullying of people holding anti-war views, including teachers — namely the above-mentioned Telegram channels «Krymsky SMERSH» and «Sevastopol. SMERSH».

Dismissals

Dismissal is the most common type of pressure on teachers who have been labelled as holding an anti-war position. Out of 148 instances of pressure, there were 82 instances of dismissal, three cases of suspension from teaching, and two involved initial suspension followed by dismissal.

Teachers were dismissed from schools (33 instances), higher education institutions (43 instances), specialised secondary education institutions (5 instances), supplementary education institutions (2 instances) and primary education institutions (one instance).

Dismissals of teachers

Article 47 of the Law «On Education in the Russian Federation» guarantees freedom of teaching, free expression of opinions and freedom from interference in a teacher’s professional activities. These freedoms, however, must be exercised in compliance with the rights and freedoms of other participants in the educational process, legal requirements and professional ethics.

In practice, the law is not followed. In 34 documented cases of dismissal, school authorities initiated pressure directly for activities conducted in the course of teaching. This is nothing but interference in the realisation of the right to freedom of teaching and expression.

Those dismissed directly for activities during classes were accused of: anti-war statements during work in writing (2 instances) and orally (12 instances), displaying anti-war materials in class (5 instances), refusing to participate in «patriotic» initiatives (13 instances), and research activities (2 instances).

In 2022, Kazan Federal University (KFU) did not renew the contract of professor Nail Fatkullin, who sent an open anti-war letter to his colleagues on 9 May. A week after he sent it out, the city prosecutor’s office issued him a «warning against violating the law». According to law enforcement officers, sending the letter contradicted the requirements of the law and goals of the university’s activities. On 20 May, Fatkullin learned that the committee did not recommend him for the position of professor of the Department of Physics and Molecular Systems. KFU’s representatives commented on the decision as follows: «There were no questions on scientometric indicators. The criticisms were in relation to political statements: in the sense of them being unacceptable ethically for an employee of the educational sphere.»

«The Academic Council considered my behaviour unethical for a professor at Kazan University. There is no document, but those were the words. The objections were solely in connection with that open letter. It went something like this: unethical political statements concerning the government, or something along those lines. In other words, there are no objections against me on science, no complaints against my teaching, ” Fatkullin shared the results of the KFU Academic Council’s meeting.

Behaviour contrary to the norms of teaching ethics or, to use the term of labour law, «committing an immoral act» is a frequent ground for dismissing teachers accused of holding an anti-war stance. Seven out of 20 interviewed teachers faced this situation: two worked in schools and five in universities.

What Is an Immoral Act?

There is a contradiction or, legally speaking, a collision between Articles 81 and 192 of the Labour Code. According to Article 192, disciplinary sanctions against an employee are allowed only for actions committed in the workplace and in connection with the performance of labour duties. At the same time, Article 81 mentions cases when actions «giving grounds for loss of trust or immoral acts were committed by the employee outside the place of work or at the place of work, but not in connection with the performance of labour duties».

Legal collisions are not uncommon. Usually, legal interpretations (e.g., resolutions of the Plenum of the Supreme Court) and judicial practice help resolve them. For example, the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation dated 17 March 2004 provides guidance on cases where an immoral act is committed outside the workplace or at the workplace but unrelated to job duties. In such situations, the employer has the right to terminate the employment contract. Therefore, if expressing an anti-war position is equated with an immoral act, it is legally possible to dismiss a teacher.

At the same time, immoral behaviour is defined as a violation of moral norms and rules of conduct in a society, as follows from court practice (Ruling of the Seventh Cassation Court of General Jurisdiction dated 5 November 2020, case No. 88-16117/2020). Consequently, the employer, when formulating the reason for dismissal in the dismissal order, must prove that the employee has violated these very norms.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) addressed this issue in its judgement in the case of former judge Olga Kudeshkina, who was dismissed under an article on committing an immoral act. Kudeshkina was removed as a judge in 2004 after she gave an interview about judicial lawlessness in the country. The qualification board used the following wording: «in order to win fame and popularity with the voters, judge Kudeshkina deliberately disseminated deceptive, concocted and insulting perceptions of the judges and judicial system of the Russian Federation, degrading the authority of the judiciary and undermining the prestige of the judicial profession.» The ECHR, in turn, noted that she had «raised a very important matter of public interest, which should be open to free debate in a democratic society» and found that her statements should have been regarded as «a fair comment on a matter of great public importance». The ECHR ruled that Russia had violated Kudeshkina’s right to freedom of expression.

The state imposes the same requirements on judges as it does on teachers, including in terms of moral character, so this ECHR judgement can be applied to cases of teachers dismissed for «immoral behaviour». Each situation of dismissing a teacher under this article should be approached with caution, considering whether such a punishment is related to the realisation of a particular person’s rights, because in many cases the reason for dismissal is their exercise of the right to freedom of speech, basic in a democratic society.

The analysis of modern Russian legislation has shown that it lacks a clear concept of «immoral act», and it is in fact the administration of an educational institution that decides in each specific case whether a teacher has committed such misconduct or not. This is a clear example of violation of the principle of legal certainty, when a teacher can be dismissed for any reason, as there are no clear boundaries and criteria of holding them responsible for this kind of misconduct.

Philologist Svetlana Drugoveiko-Dolzhanskaya was fired from Saint Petersburg State University after she acted as a defence expert in the criminal case of anti-war activist Sasha Skochilenko and pointed out the mistakes committed by her colleagues on the prosecution side. The university’s ethics commission reviewed the case. According to the university, Drugoveiko-Dolzhanskaya «repeatedly spoke sarcastically about the competence of her colleagues». The commission concluded that she had violated «moral and ethical norms» and that her actions were incompatible with her work at the university.

Other immoral offences also attributed to teachers included: broadcasting anti-war slides by Aleksandr Boburov, a school teacher in the Moscow region; anti-war posts published by Roman Melnichenko, an employee of Volgograd State University, and Marina Dmitrievskaya, an employee of the Russian State Institute of Performing Arts; as well as the participation in anti-war protests of Denis Skopin, a lecturer at Saint Petersburg State University, and Kamran Ramiz Manafli, a teacher at a Moscow school.

One interviewee revealed that a teacher dismissed under the article on immoral conduct is then «blacklisted». If they attempt to return to teaching, this record will prevent them from being hired. Individuals dismissed under this article are effectively barred from working as teachers in Russia. However, even if someone is dismissed on other grounds, finding a new job will still be difficult, as potential employers will likely contact the previous school to inquire about the teacher.

This interviewee was also dismissed for an «immoral act». In his words, the school administration demanded he delete his anti-war post under the threat of dismissal, but he replied that his «honour is more important» and agreed to resign. Despite the agreement, he was not allowed to enter the school the following days and was ultimately dismissed for an «immoral act». Later, the teacher learned that the administration had held a meeting with staff, students, and their parents. At the meeting they claimed that the dismissed teacher had «manipulated everyone», labelled him a «traitor to the country» working for the U.S. and supporting “ extremist Navalny».

Nine university lecturers interviewed for this study revealed that they were employed on temporary contracts, and when the management decided to part ways with them, their contracts were simply not renewed. One lecturer noted that this practice is common in almost all Russian universities. In his words, it is easier to control staff that are on temporary contracts; at his school, the non-renewal of contracts served as a tool to pressure employees who were not loyal to the administration.

Being dismissed is often a difficult experience for a teacher psychologically, even when it involves voluntary resignation. The situation becomes significantly more complicated when the dismissal is recorded as one «for an immoral act», which effectively bans the individual from working within the Russian education system. Dismissed teachers are left with two alternatives: transitioning to private tutoring or building a career abroad.

Denunciations

In 51 out of 148 cases analysed, the pressure began with a denunciation — a deliberate report to the relevant authority that a teacher held anti-war views to pressure them. Therefore, cases where hostile individuals published information about a teacher to a wide audience were not included in the statistics on denunciations — this type of pressure is classified as cyberbullying.

Who Are the Targets of Denunciations?

Nearly 50% of denunciations are directed at school teachers. University lecturers account for approximately 27% of all denunciations. The remaining cases involve employees of vocational schools (8%), supplementary education institutions (14%), and a kindergarten (2%).

Who Are the Authors?

Students and their parents were responsible for a significant share of the denunciations (22 out of 51). Colleagues (4 instances), managers (4 instances), and pro-war activists (3 instances) also submitted denunciation reports against teachers. In three instances, teachers’ acquaintances with no connection to education authored the denunciations. In another, the authors were members of parliament to whom a teacher appealed with her anti-war letter.

In two cases, multiple individuals filed denunciations against teachers. Dmitry Rudakov, an employee of Omsk State Technical University (OmSTU), was dismissed based on an internal memo stating that he had said during a lecture that he «would have moved to the U.S. but stayed to watch OmSTU and Russia collapse», alongside complaints from three students who claimed that he «expresses his personal negative political views during classes […] imposing them on students», «actively speaks out against patriotism», and «posts anti-Russian news on social media». Mathematics teacher from Moscow Tatyana Chervenko was the target of several denunciations from a woman unknown to her (presumably a pro-war activist). The woman filed complaints with the school administration, the Department of Education, and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova. The reason was an interview Chervenko gave to the German outlet Deutsche Welle, in which she discussed how schools were changing in the context of the war. Later, Chervenko gave an interview to the TV Rain channel, where she criticised «Important Conversations»; after that, the head of the school union reported her to the management.

There are also double or «chain» denunciations, where a teacher is first reported to one authority (for instance, a school principal), who in turn authors the next one — to law enforcement, for example. Out of 51 instances analysed, we identified five clear cases of «chain denunciations». In four of those, the denunciation led to administrative prosecution. For example, in the spring of 2023, police drew up an administrative offense record against Svetlana Vshivkova, an art teacher from the village of Bolshebrusyanskoye in the Sverdlovsk region under the article on «discrediting» the military. Parents first complained to the school principal about her anti-war remarks. The principal in turn reported her to the Federal Security Service (FSB). In July 2023, the Beloyarsky District Court of the Sverdlovsk region found Vshivkova guilty and fined her 30,000 rubles (300 USD).

Unsurprisingly, school teachers have been the primary targets of denunciations from students’ parents. In seven instances parents filed denunciation reports with law enforcement and in three cases they reported teachers to the school administration. In one case, parents submitted denunciation reports both to the school principal and the police, leading to the administrative prosecution and dismissal of Susanna Bezazieva, a teacher from Dzhankoy (Crimea). In April 2022, she overheard students discussing the war and intervened to say that Ukraine had no intention of attacking Russia.

In three cases, however, it was the students themselves who reported their teachers. In Astrakhan, students complained to the school principal about their mathematics teacher Elena Baibekova for «political discussions during classes». English teacher Lyubov Kozlova from Yuzhnouralsk was reported for making negative comments about the war — students complained to another teacher, who then passed it on to the school administration. In another instance, students contacted pro-war activists: they sent a video of Crimean chemistry teacher Linara Rasulova singing the Ukrainian national anthem and «Chervona Kalyna» to the «Krymsky SMERSH» Telegram channel, which led to her being bullied.

When it comes to universities, in nine out of the ten cases, students themselves wrote denunciation reports against university lecturers. The exception is the case of Evgenia Paigina. In her words, the mother of one of her students, who had poor grades, called the emergency services and reported alleged anti-war remarks made by Evgenia during her lectures. In the other cases, students either complained to law enforcement (5 instances) or the university administration (2 instances). In the case of two lecturers from Moscow International University, Konstantin Miroshnikov and Vladimir Sukhoi, a student reported them to pro-war blogger Sergey Kolyasnikov, which led to their being bullied.

In the remaining seven instances, the authors of the denunciations are unknown.

What Prompts Denunciations?

Of all denunciations, 57% were based on oral remarks during lessons or in the presence of students. In some cases, the teachers deny that these conversations took place at all. Amur State University lecturer Yevgenia Paigina was fined 30,000 rubles (300 USD) under the article on «discrediting» the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for allegedly saying in class that «soldiers of the Russian Federation are waging an occupation war on Ukrainian territory, killing civilians and blowing up kindergartens and schools». She later claimed that she had said nothing of the sort, suggesting that students might have been retaliating against her for giving low grades.

Oral remarks led to 16 denunciations against school teachers (14 of which were made either by students or their parents) and 10 denunciations against university lecturers (nine by students and one by a student’s parent).

The next most common subject of denunciations are posts and messages on the internet, accounting for about 14% of the cases. In many of these instances, the denunciations were made against the backdrop of ongoing conflicts or dissatisfaction of parents with the teacher’s style, stance, etc. One example is the case of Vasily Razumov, a literature teacher at an Orthodox school in Yaroslavl. Parents complained to the school administration about his teaching methods, which triggered an extraordinary meeting of the school’s education council. The administration managed to defend the teacher at the meeting, but he was nevertheless fired after the denunciation that followed.

Teacher anti-war activism, be it at work or outside of it, accounts for 12% of denunciations. Examples include actions such as opposing pro-war banners, as in the case of Alyona Podlesnykh from Perm and distributing leaflets, as in the case of the teacher couple Alyona and Grigory Ishimtsev from the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

Another 8% of cases are denunciations made after oral remarks during conversations with colleagues. For example, Gennady Tychina, a teacher from St. Petersburg, told a school security guard that he was proud of his Ukrainian heritage.The school administration then began pressuring him to resign. The next day, during his lesson with fifth-graders, the school principal came in with two armed police officers to detain him. He was charged with disorderly conduct (Article 20.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for allegedly using foul language in the street.

In 4% of denunciations, teachers are accused of refusing to conduct «patriotic» events. As detailed in the previous chapter, this happened to the principal of School No. 12 in Perm Elena Rakintseva, who refused to hold «Important Conversations» lessons with participants of the war as guests. «Prikamskiye Knights» movement activists bullied her, whilst securing support of the local education department.

In two instances, the denunciations were prompted by displays of anti-war materials on school premises, in another, public statements in the media, and in yet another case, comments in a chat with students. For example, colleagues accused Olga Lakhman from Orsk of sending them the Wikipedia article titled «Russian invasion of Ukraine», which they posted on their information board without checking its content.

In 8% of cases, a single denunciation was made on multiple grounds. For example, informants accused Vladimir Kaluzhsky, the head of the Department of Children and Youth Music at the Novosibirsk State Philharmonic, of attempting to stage a concert based on a story written by a Ukrainian writer and liking his son’s «anti-Russian» posts.

Conclusions

Denunciations preceded at least a third of known prosecutions, highlighting the significant role that this instrument of pressure plays in targeting teachers.

63% of denunciations were based on oral remarks made in conversations with students or colleagues, and in over half of these cases, they were not corroborated by audio or video recordings. Nevertheless, in all of these cases, the denunciations led to either a dismissal or administrative or criminal prosecution. Claims by informants about teachers’ anti-war statements, even without evidence, resulted in nine dismissals and nine administrative offence cases. In total, 18 teachers were affected, with two of them both dismissed and prosecuted.

As for the criminal cases triggered by denunciations, there is no information on whether they include audio or video evidence. Therefore, we cannot confirm whether such evidence exists or not.

We can conclude that the management of educational institutions considers a denunciation to be sufficient grounds for dismissing a teacher, and law enforcement agencies, to press administrative charges. However, the lack of data prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions about the role of denunciations in criminal prosecutions.

Are Denunciations Becoming Less Frequent?

In 2022 and 2023, the number of denunciations was nearly the same — 28 and 22 instances, respectively. In 2022, the majority of instances (17) involved school teachers, while the rest concerned university lecturers, vocational educators and supplementary education staff. In 2023, out of 22 denunciations, only six were directed against school teachers, seven against university lecturers and the remainder against other categories of educators.

We only documented one denunciation in the first seven months of 2024, directed against Natalia Taranushenko, a school teacher. According to her, she faced denunciations since 2022, but the consequences, in the form of a criminal case, manifested themselves only this year.

Consequences of Pressure on Teachers for Expressing Anti-War Views: Emigration

Pressure on teachers in some instances leads to emigration. The main reasons for leaving the country include the inability to continue their career in Russia and criminal prosecution. According to open sources, out of 148 teachers who faced persecution due to their imputed anti-war stance, 22 emigrated. Five of these 22 teachers left the country escaping criminal prosecution.

Why Are Teachers Leaving?

Some teachers have publicly discussed their emigration. Most commonly, they cite fear for themselves and their loved ones due to pressure from the security forces as the driving factor. For example, Elena Baybekova, a teacher from an Astrakhan school, participated in an anti-war picket. Subsequently, the Federal Security Service officers came to her workplace and demanded that she come to the Center for Combating Extremism. Soon after, law enforcement officials came to her home to bring her to court, charging her with disobeying a police officer (Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). She received five days’ detention. Police then detained her again to hold a conversation with the local police chief. After that, she left the country. In an interview, Baybekova said that she had never planned to emigrate but was driven to do so by the pressure from the security forces and fear for her son, who could be drafted into military service.

Another university teacher, Alyona Podlesnykh from Perm, attributed her departure not only to repression but also to societal pressure: «We understood that staying in Russia was dangerous not only because of the mobilisation. The country had begun to see aggressive actions against those who disagreed with the war, both from the authorities and from citizens supporting the regime.» The teacher was subjected to harassment after war supporter Zakhar Prilepin wrote about her protest against a banner with the letter «Z” that had been hung on the House of Officers building, a cultural heritage site.

Aleksandr Saifullin, a teacher from a Moscow vocational school, decided to leave Russia due to anonymous threats that began coming in after a student posted a video from his «Important Conversations» lesson, at which Saifullin spoke openly about the war. «My friend told me, ‘You need to leave right now.’ In a moment of reckless spontaneity, I bought a ticket to Istanbul for 10 October, ” the teacher recalled.

Boris Romanov, a school teacher from St. Petersburg, managed to leave Russia despite criminal charges. He was in pre-trial detention on charges of «fakes» about the Russian army (Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code). When he was released from detention with a ban on certain actions pending trial, he went to Germany and asked for political asylum. Romanov said he decided to leave because he had to take care of his family and because he would do more good out of jail. «Before 24 February, I wasn’t thinking about leaving. I thought we still have a constitutional form of government in Russia, and that means above all certain freedom of speech. [It is] a basic category, a basic right, without which public life is impossible», Romanov remembered.

Not all the teachers who left Russia feel safe in emigration. Natalya Taranushenko, a school teacher from a town near Moscow, faced prosecution on charges of «fakes» about the Russian army for statements she made at a homeroom lesson at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. She learned about the criminal charges against her in June 2024. According to the teacher, she had to make the decision to leave in a state of fear and confusion. Taranushenko left for Armenia, and in July she was detained while trying to take a flight out of the country because Russia issued an international arrest warrant against her.

Taranushenko noted that Armenian police officers were polite with her. «Despite their good treatment, I was scared. It was a very difficult, exhausting day. It is horrible to find yourself a wanted criminal. I have always been a law-abiding person, and now I have become a persecuted felon, ” the teacher recalled. After four hours of detention she was released. According to the latest information, she remains in Armenia and is receiving help from human rights defenders.

A similar thing happened to Natalya Narskaya, a vocal instructor from Lyubertsy, a town outside Moscow. After the beginning of the full-scale invasion, she sent a letter to the municipal administration criticising the actions of the Russian army. Municipal deputies reported her to the police. After a visit from law enforcement, Narskaya made an urgent decision to emigrate to Kazakhstan, since she did not have a travel passport. In April 2023, Narskaya was charged with extremism (Part 2 of Article 282 of the Criminal Code) and calls for extremist activities (Part 2 of Article 280 of the Criminal Code) for publishing posts that allegedly incited hatred towards Russian servicemen. Russia issued an international arrest warrant against her in June and ordered her arrest in absentia. Soon, Almaty police officers paid her a visit, but did not find her at home; then she turned herself in to law enforcement. She was detained and placed in a pre-trial detention centre despite her mental illness, but was released in July 2024. As of August 2024, her whereabouts and status are unknown.