11 Years of Occupation: Establishment of the Repressive Regime in Crimea

Eleven years ago, Russian authorities illegally occupied Crimea. Since then, the peninsula According to our data, as of 2024, Crimea has recorded the highest number of politically motivated criminal and administrative cases, as well as the highest rate of politically motivated detentions per 100,000 people compared to any Russian region. Since 2014, we have documented 349 individuals prosecuted in politically motivated criminal cases in Crimea and Sevastopol. This number is higher only in Moscow, where the population is five times that of Crimea. Many of those targeted by Russian authorities are Crimean Tatars. Beyond criminal and administrative prosecutions, local residents have also faced other forms of repression, including forced disappearances and torture.

In this report, we use the terms «occupied» and «occupation» in line with the terminology adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in relation to Crimea. These terms aim to emphasise the international community’s non-recognition of Russia’s unlawful annexation of Crimea.

Here we present a periodisation of the establishment and development of Russia’s repressive regime in occupied Crimea. In this report, we examine how Crimean Tatars became the most persecuted group on the peninsula. We also consider how repressions in Crimea have transformed since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The goal of this report is to analyse how the repressive regime in Crimea was established and how it has evolved over 11 years. We also aim to compare the repression in Crimea with the situation in other Russian regions.

This study is based on data and analysis from OVD-Info, as well as on data from other organisations such as Crimean Solidarity, an independent human rights project «Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial», the Memorial Human Rights Centre, the Human Rights Centre ZMINA, the CrimeaSOS project, and the publications of Crimea.Realities. Since the occupation of Crimea, human rights activists from Ukraine, Russia and international organisations have documented and published a large number of studies of mass human rights violations on the peninsula. We highly appreciate the work of our colleagues and hope that our analysis will also contribute to the understanding of repression in Crimea. We also hope to attract additional attention and support for the victims of political persecution. We express a special gratitude to the volunteers of OVD-Info for their participation in the search for information for this report.

By the time Russia occupied Crimea, Russian authorities had already gained extensive experience in carrying out repression in their own country. In 2014, trials as part of the Bolotnaya case were still ongoing in Moscow and the government had already passed the laws on «foreign agents».

A Period of Transition: Establishment of the Infrastructure of Repression (2014–2015)

Enforced Disappearances

Even before the referendum on «accession to Russia» in 2014, pro-Ukrainian activists, journalists, and Crimean Tatars disloyal to the Russian authorities began to disappear in Crimea. Between March 2014 and November 2020, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights documented 43 instances of enforced disappearances in Crimea. In most instances, the abducted individuals were later released, one Crimean resident remained in custody and another kidnapped individual was found dead. As of November 2020, the fate of 11 abducted Crimean residents remained unknown.

Facts about some of the abductions in Crimea

- The CrimeaSOS project identifies two distinct periods of abductions in Crimea prior to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022: from March to May 2014, associated with the crackdown on journalists and activists during the occupation, and from the summer of 2014 onward, when the persecution intensified as part of repression carried out against Crimean Tatars and pro-Ukrainian civil activists.

- The first documented victim was Reshat Ametov, a Crimean Tatar and supporter of Ukraine’s unity. He was abducted by unidentified men in camouflage during a peaceful rally in Simferopol on 3 March 2014. Less than two weeks later, on 15 March, a passerby discovered Ametov’s dead body showing signs of torture. Those responsible for the crime were never found.

- At least six Ukrainian and foreign journalists who had come to the peninsula to cover the occupation of Crimea became victims of enforced disappearances during the first period.

- Timur Shaimardanov disappeared on 26 May 2014. He had been involved in the pro-Ukrainian activities of the Ukrainian People’s House initiative and was helping to deliver humanitarian aid to Ukrainian soldiers in Crimea. He received threats shortly before his abduction. Four days later, Shaimardanov’s acquaintance Seyran Zinedinov, who tried to locate him, also went missing. The investigation launched in 2014 was suspended in 2017. As of March 2025, the whereabouts of both Shaimardanov and Zinedinov remained unknown.

- Valentyn Vyhovsky, a Ukrainian citizen and participant in the Euromaidan movement, disappeared in Crimea on 17 September 2014. He was detained by the Federal Security Service (FSB) upon entering the peninsula, secretly held for several days and then transferred to Russia. He was initially charged with commercial espionage (Article 183 of the Criminal Code), but the charge was later reclassified as espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code). In 2015, the court sentenced Vyhovsky to 11 years in a strict-regime penal colony. He stated that he had confessed under torture, which included beatings and a mock execution. According to Vyhovsky, the charge was reclassified as a more serious one after he refused to cooperate with Russian intelligence services. In 2016, he was transferred to a penal colony. Russia has refused to hand him over to Ukraine.

- In August 2015, Mukhtar Arslanov, a resident of Simferopol, went missing. According to his sister, a witness saw two men in uniform abducting him. In April 2024, Mukhtar Arslanov’s name appeared on Russia’s Federal Financial Monitoring Service list of extremists and terrorists, which may indirectly suggest that Mukhtar is alive and held in captivity on charges of extremism or terrorism.

people became victims of enforced disappearances in Crimea between 2014 and 2022

According to UN data

Enforced disappearances in Crimea were carried out both by paramilitary groups supported by Russian authorities but not formally affiliated with them at the beginning of the occupation — such as the «Crimean Self-Defence», Cossack groups, the «Crimean Liberation Army» and the political party Russian Unity — as well as by Russian government agencies, such as the FSB, the police and the Investigative Committee.

In the first year of the occupation of Crimea, paramilitary groups and law enforcement officers frequently abducted pro-Ukrainian activists and journalists

First Politically Motivated Criminal Cases

Soon after the occupation of Crimea, law enforcement officers began initiating criminal cases against people who did not support the occupation, charging them with terrorism and extremism; at least one case of espionage was also opened. In 2014, at least 12 people were charged in politically motivated cases; in 2015, the number of new defendants nearly doubled, reaching 20.

Dynamics of the number of defendants in criminal cases by year

The first high-profile political prosecution in Crimea in 2014 was the case of the so-called «Crimean terrorists». At the time, the FSB charged four activists with setting fire to the offices of the United Russia party and the Russian Community of Crimea in Simferopol, as well as with planning to blow up the Eternal Flame and a monument to Lenin in the city.

The Beginning of Prosecution in Cases Related to Hizb ut-Tahrir

Operating on the occupied peninsula, Russian law enforcement officers resorted to various practices of initiating politically motivated criminal cases they had previously tested in Russia. In particular, they used criminal charges that could be applied to broad groups of people, thereby partially bringing repression to a systemic level. One of the most frequently used tools of this kind has become the bringing of charges for involvement in the activities of the Islamic party Hizb ut-Tahrir, which was declared a terrorist organisation in Russia in 2003. In Ukraine, the party operated legally — before the Russian occupation, the Ukrainian authorities did not initiate any criminal cases related to its activities on the territory of Crimea.

According to OVD-Info analysis, the share of cases against Hizb ut-Tahrir supporters ranged from 6% to 12% of all politically motivated criminal prosecutions in 2012-2013.

The share of politically motivated prosecutions related to involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir increased after the occupation of Crimea

Russian law enforcement officers initiated the first prosecution for alleged involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir on the peninsula in early 2015. It later became known as the case of the so-called «Sevastopol group».

This case opened the way for mass repression against Muslims in Crimea, which predominantly affected Crimean Tatars.

Human rights defenders believe that the cases related to Hizb ut-Tahrir were politically motivated. The Human Rights Centre Memorial and, after its liquidation, the independent human rights project «Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial» have been monitoring criminal prosecutions by Russian authorities for alleged involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir for years. According to the lists of political prisoners maintained by the project, during the monitoring period, 412 individuals have been charged in such cases across Russia, the occupied Crimea and Sevastopol.

According to Memorial’s assessment, law enforcement officers regularly fabricate criminal cases of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir based on non-existent crimes. The individuals prosecuted under terrorism-related articles are charged not with violent actions, but solely with having links to the party. The prosecution commonly uses unreliable evidence, such as secret witnesses or literature planted by law enforcement during searches. Furthermore, the punishments imposed for the alleged crimes are disproportionately severe — up to 20 years of imprisonment and, in instances that include charges of organising the activities of a terrorist organisation, up to life imprisonment. Government propaganda, which exploits the widespread Islamophobia in society, also works against the prosecuted, Memorial notes.

Suppressing Freedom of Assembly

Another measure by means of which Russian authorities established repressive practices throughout the peninsula was the suppression of freedom of assembly and the prosecution of participants in popular gatherings on charges of organising mass riots and using violence against representatives of the authorities.

For instance, on 26 February 2014, two rallies were held in front of the building of the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea (Crimea’s legislative body). One of them was initiated by Russian Unity, which supported Crimea’s accession to Russia. The participants in the second rally, organised by the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars, planned to disrupt the meeting of the Verkhovna Rada of the peninsula, where a decision could be made to hold a referendum on Crimea’s status. The conflict between the participants of the pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian rallies escalated into clashes, resulting in a stampede that left 30 people injured and two people dead.

Due to the protests, the Verkhovna Rada postponed its proceedings. A year later, the Russian Investigative Committee initiated a criminal case following the events of 26 February, thereby extending Russian law to the period before the so-called referendum (and consequently, before the integration of the occupied territory into its jurisdiction).

Another milestone rally took place on 3 May 2014. A month before that, Russian authorities banned Mustafa Dzhemilev, the leader of the Crimean Tatar national movement, a member of the Verkhovna Rada, the chairman of the Mejlis from 1991-2013 and a well-known Soviet dissident, from entering the country, and this ban was extended to Crimea. The Crimean Tatar community perceived this ban as an attempt by Russia to isolate the popular public figure influential on the peninsula. On 3 May, Dzhemilyev’s supporters gathered at the administrative border with Crimea to meet the leader of the movement as he tried to return to the peninsula. The situation escalated when the protesters broke through the Russian military cordon at the border checkpoint in Armyansk, leading to clashes with law enforcement agencies, including Berkut (a special police force) officers. In response to these events, Russian authorities initiated criminal cases against the protesters.

Government propaganda publicly portrayed pro-Ukrainian Crimeans as dangerous violent offenders and mass rioters. At the same time, the release of the individuals involved in the 3 May case on bail indicates that initially, in some cases, the Russian authorities attempted to use softer forms of influence on their opponents while establishing their repressive regime on the peninsula.

Attacks on Media and Associations

Along with suppressing freedom of assembly, Russian authorities began to systematically attack other institutions of civil society. Media and independent civil organisations have also been targeted.

As early as March 2014, the Centre for Investigative Journalism already recorded 85 instances of violations of journalists’ rights, including physical assaults and beatings, restrictions of access to public information and acts of censorship. In February and March, Russian authorities forced Ukrainian media outlets out of television and radio broadcasting on the peninsula and took control of the peninsula’s largest television centres — the Crimea State Broadcasting Company and the Yalta TV and Radio Company. Many Ukrainian Internet resources were also blocked, including those that were not formally banned by Russian legislation.

Roskomnadzor (Russia’s main governmental body responsible for media regulation) has ordered local media outlets to re-register in accordance with Russian legislation. According to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists’ Rights, 92% of media outlets operating in Crimea before the occupation were not re-registered under the new rules. In addition to these bureaucratic and organisational restrictions, Ukrainian and foreign journalists have also been periodically banned from entering the peninsula.

In February 2015, one of the first criminal cases against journalists in Crimea was initiated — against Anna Andrievskaya. The journalist was charged in absentia with calls to violate the territorial integrity of Russia (Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code). Criminal prosecutions of journalists became more frequent later on. In 2023, the human rights organisation CrimeaSOS published a list of 19 professional and civic journalists who had faced prosecution by Russian authorities in Crimea starting from 2014. Of these, 16 were in captivity at the time.

The closure of the Crimean Tatar TV channel ATR and prosecution of its employees was another key milestone in the restriction of media freedom in occupied Crimea.

- In 2015, the Ukrainian TV channel ATR, one of the three Crimean TV channels broadcasting in the Crimean Tatar language, stopped broadcasting after Roskomnadzor refused to issue a licence for the outlet. During the illegal annexation of Crimea, the channel advocated for the territorial integrity of Ukraine and broadcast live the events in Crimea at the time. Roskomnadzor cited incorrectly completed documents as the official reason for the closure and denied any political motives in its actions. Representatives of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people stated that the refusal to register the channel violated Article 16 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- In Simferopol, officers of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation conducted a search of the apartment of the ATR TV channel operator Eskender Nebiev on 21 April. He was detained afterward and arrested the following day. Nebiyev was charged with participating in mass riots on 26 February 2014 (Article 212 of the Criminal Code). On 12 October 2015, Nebiyev was sentenced to two and a half years of suspended imprisonment.

- In November 2015, a series of searches were conducted in the ATR headquarters, as well as in the homes of the channel’s employees in Crimea and Moscow, in connection with the criminal prosecution of the channel’s director-general Lenur Islyamov.

During this period, Ukrainian organisations were being forced out of the Crimean non-profit sector and replaced by Russian ones. NGOs that had previously operated on the peninsula were required to re-register in accordance with Russian legislation. In a number of cases, the Russian Ministry of Justice refused to register Crimean organisations, citing formal errors in the documents. At the same time, some pro-government Russian NGOs began opening their branches in Crimea and taking the place of the closed Ukrainian ones. Examples of such organisations include the Association of Lawyers of Russia, Officers of Russia, Business Russia, and «Opora Rossii» («Pillar of Russia», an NGO focused on supporting small and medium enterprises). In addition, the new authorities created and supported pro-Russian movements of Crimean Tatars.

Russian authorities also began to criminalise independent associations. One of the important stages on this path was the declaration of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis an extremist organisation. Although it happened in 2016, the persecution of the Mejlis began back in 2014. The Mejlis was one of the first public organisations to be given such a status, which effectively turned all its employees into outlaws. On the one hand, this corresponded to the general tendency of the Russian authorities to suppress socio-political organisations that were critical of their actions, and the application of the anti-extremist legislation to such an organisation in occupied Crimea may be motivated by their desire to more harshly suppress civil society on the peninsula. On the other hand, opposition civil activity in Crimea after 2014 was conducted predominantly by the Muslim national-ethnic group of Crimean Tatars. At that time, anti-extremist or anti-terrorist legislation was already being intensively applied against various religious minorities in Russia. The authorities would later begin to use anti-extremist legislation against Russian political and public associations. Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation would be the first to be banned this way in 2021.

— In September 2014, searches were conducted in the headquarters of the Mejlis and the homes of the organisation’s members and activists. Law enforcement officers arrested the deputy head of the Mejlis Akhtem Chiygoz on charges of organising riots on 26 February.

— In 2014, Russian authorities banned the leaders of the Crimean Tatars Mustafa Dzhemilev and Refat Chubarov from entering Crimea. In 2015, Russian authorities forcibly expelled the activist of the Crimean Tatar national movement Sinaver Kadyrov from the peninsula.

— In May 2015, the prosecutor’s office warned members of the Mejlis about the «inadmissibility of violating Russian legislation». This happened just before the gatherigns planned for 18 May — the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide. A month later, a member of Mejlis, Dilyaver Akiyev, received a notice from the Crimean prosecutor’s office recommending not to hold any events on the Day of the Crimean Tatar Flag, which is celebrated on 26 June.

— In May 2015, the FSB initiated a criminal case against the head of the Mejlis Refat Chubarov for calls to violate the territorial integrity of the country (Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code). Chubarov was subsequently arrested in absentia and later sentenced, also in absentia, to six years in prison under this article and on charge of organising mass riots (Part 1 of Article 212 of the Criminal Code) in connection with the events of 26 February 2014.

— In January 2016, information appeared about a criminal case initiated against Mustafa Dzhemilev. For more information, read the section, «What happened to the participants of the rally of May 3?». In addition, Russian authorities put pressure on Dzhemilev’s relatives who still lived in Crimea at the time.

— On April 26, 2016, the Supreme Court of Crimea officially declared the Mejlis an extremist organisation and banned its activities in Russia and Crimea. Recognising the Mejlis as an extremist organisation has put about 2.5 thousand of its members at risk of direct prosecution.

— In March 2017, the Human Rights Centre Memorial, jointly with the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre and the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, filed a complaint with the ECHR in the interest of the Mejlis. There has been no decision on the case as of this writing.

Since the beginning of the Russian occupation of Crimea, the Russian state has pushed against society in a wide variety of areas on top of using direct repression. For example, the situation with LGBT+ rights on the peninsula has worsened, Russian authorities have restricted education in the Ukrainian language, and some residents of the peninsula have been forcibly granted Russian citizenship.

An Established Repressive Regime (2016-2021)

By 2016, the establishment of a functioning repressive infrastructure in Crimea was complete, suppressing assemblies, media and independent associations, as well as prosecuting opponents of the authorities, activists, journalists and human rights defenders. This period has seen an increase in the number of politically motivated prosecutions, in some cases involving torture and harsh conditions of detention, as well as intensified pressure on lawyers and human rights defenders.

Large-scale Prosecutions in Cases of Hizb ut-Tahrir and Criminal Cases against Activists of Crimean Solidarity

In 2016, the number of new politically prosecuted individuals in Crimea reached 38, with almost half of them prosecuted on charges of association with Hizb ut-Tahrir. At the time, law enforcement officers periodically conducted mass raids against Crimean Muslims who were charged with involvement in the party’s activities. Subsequently, human rights activists would give these prosecutions names based on the localities where the defendants were detained: hence, they are now known as the cases of the Yalta group, the First Bakhchisaray group and the Simferopol group.

Prosecutions on charges of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir reached their peak in 2019, when Crimea initiated such prosecutions against 37 people. During the pandemic, the scale of repressions in relation to Hizb ut-Tahrir cases slightly decreased: prosecutions in Crimea were initiated against 12 people in 2020 and 10 people in 2021. A total of 127 people are currently known to be prosecuted in Crimea and Sevastopol on charges of association with Hizb ut-Tahrir and 106 of them are imprisoned.

The largest number of cases as part of persecuting Hizb ut-Tahrir in Crimea were initiated in 2019

Unlike the prosecution of defendants in Hizb ut-Tahrir cases in Russia, in Crimea such repressions are directed not only and not so much against representatives of the movement associated with Islam, but against a civically active group of Crimean Tatars disloyal to the Russian authorities.

The prosecution of Crimean Muslims on charges of cooperation with Hizb ut-Tahrir follows the same pattern. A person or a group of people are taken into custody (in exceptional cases placed under house arrest), charged with membership in the party or organisation of its activities, the prosecution involves loyal linguistic experts and secret witnesses, after which the court hands down a guilty verdict.

The prosecution on charges of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir’s activities provided an opportunity for Russian authorities to use anti-terrorism legislation to suppress Crimean activists and destroy their horizontal ties and solidarity. Despite this, in April 2016, an association of the wives and other relatives of political prisoners, as well as lawyers, was established. It meets monthly to discuss the trials and seek ways to influence the surrounding circumstances. Its meetings later began to gather 100-120 people and over time the movement evolved into the human rights platform Crimean Solidarity.

Russian authorities launched repressions against Crimean Solidarity. As a result, many of its members themselves began facing charges in cases of Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Among the defendants in politically motivated criminal cases in Crimea and Sevastopol, the highest number of individuals are prosecuted in cases of Hizb ut-Tahrir

Other Politically Motivated Criminal Cases

In addition to charges of association with Hizb ut-Tahrir, there is one known case in which Russian authorities charged Crimean Tatars with participating in the activities of Tablighi Jamaat, a Muslim religious organisation declared extremist in Russia in 2009. At the time of the occupation of the peninsula, the organisation operated legally in Ukraine.

- On 2 October 2017, searches were conducted in several districts of Crimea, leading to the detention of four local residents. Russian law enforcement agencies charged them with involvement in Tablighi Jamaat, and in 2019, they were convicted for participation in an extremist organisation (Article 282.2 of the Criminal Code). Renat Suleymanov was sentenced to four years in a penal colony (released in 2021), while Talyat Abdurakhmanov, Arsen Kubedinov and Seyran Mustafaev received suspended sentences.

Throughout the occupation of Crimea, 349 individuals have been prosecuted in politically motivated criminal cases

Law enforcement officers also charged Crimean Tatars with common criminal offences, as seen in Vedzhie Kashka’s case.

- In November 2017, 82-year-old Vedzhie Kashka passed away following an attempted arrest. Her lawyer Nikolai Polozov, who later sought to hold those responsible for her death accountable, reported that during the attempted arrest, Kashka was struck with a rifle stock at least once.

- On 23 November 2017, Russian law enforcement officers in Simferopol detained the Crimean Tatar activists Asan Chapukh, Bekir Degermendji, Kazim Ametov and Ruslan Trubach. According to the detainees, they were attempting to help Vedzhie Kashka recover money that had been fraudulently taken from her by a Turkish citizen. However, Russian authorities in Crimea turned this claim against the activists, charging them with extortion (Part 2 of Article 163 of the Criminal Code). Chapukh was later also charged with illegal possession of weapons (Article 222 of the Criminal Code). The court sentenced the defendants to suspended sentences ranging from three to three and a half years. However, their health was severely affected during their time in pre-trial detention — Chapukh suffered a mild stroke, while Degermendji’s chronic asthma worsened. The lawyer Polozov initiated an independent investigation into Vedzhie Kashka’s death, but the Russian Investigative Committee found no grounds to prosecute the law enforcement officers responsible for her death.

Since 2018, cases on charges of participation in the Noman Chelebidzhikhan Volunteer Battalion have started emerging in the territory of the occupied peninsula. Over time, such a charge is becoming an increasingly popular type of political persecution.

- The Noman Chelebidzhikhan Crimean Tatar Volunteer Battalion was founded in 2015 amid the food and civil blockade of Crimea and was responsible for monitoring freight at the administrative border.

- In September 2015, the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People initiated an indefinite action to prevent freight transport from Ukrainian territory into the Russia-occupied Crimea. Participants in the civil blockade of Crimea demanded, among other things, that Russian authorities release Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar activists, stop persecuting Crimean Tatars, ensure freedom for Ukrainian media and foreign journalists, and lift the ban on entry for the leaders of the Crimean Tatar people. The action took place at the border of the peninsula with Ukraine’s Kherson region, at the checkpoints of Chongar, Chaplynka, and Kalanchak. Participants set up roadblocks with concrete blocks, halting the movement of trucks while allowing pedestrians and passenger vehicles to pass through unhindered. At the end of 2015, the coordinator of the food blockade Lenur Islyamov announced its cessation following the Ukrainian government’s decision to ban the supply of goods and services to occupied Crimea.

- According to human rights defenders, the Noman Chelebidzhikhan Battalion was more of a public association operating at the border with Crimea with the knowledge of Ukrainian authorities, rather than an armed group. In 2016, members of the battalion started to patrol the border as part of the public association «Asker» together with the Ukrainian Border Guard Service, without engaging in combat. Several years later, Russian authorities accused former or alleged members of participating in an «illegal armed formation». Key evidence in these cases is often based on media publications, testimonies of secret witnesses or statements made by other convicted individuals who are coerced into cooperating with the investigation.

- The first cases based on such charges included the cases of Fevzi Sagandzhi, Dilyaver Gafarov and Medzhit Ablymitov. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the volunteer battalion was declared a terrorist organisation in Russia, and the number of people prosecuted on charges of their alleged ties to this battalion skyrocketed, extending beyond Crimea to the occupied territories of Ukraine’s Kherson region.

Notable among other politically motivated prosecutions from 2016 to 2021 are cases initiated on charges of various types of sabotage. Such charges have been directed both at the disloyal and socially active group of Crimean Tatars, as seen in the case of the gas pipeline explosion, as well as at random people who were portrayed by Russian authorities as evidence of a military or terrorist threat (the so-called cases of «Crimean saboteurs»).

- Nariman Dzhelyal, a former deputy head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, and brothers Asan and Aziz Akhtemov were prosecuted in the case of the gas pipeline explosion. They were charged with sabotage (Part 2 of Article 281.2 of the Criminal Code), storage of explosives (Part 4 of Article 222.1 of the Criminal Code) and smuggling explosive devices (Part 3 of Article 226.1 of the Criminal Code). According to the investigation, they were involved in the explosion of the gas pipeline in Crimea in August 2021. According to the defendants, they confessed under torture. In September 2022, Dzhelyal was sentenced to 17 years in a strict-regime penal colony, and the Akhtemov brothers received 13 and 15 years in a strict-regime penal colony respectively. In June 2024, Nariman Dzhelyal was released as part of a prisoner exchange between Russia and Ukraine.

- The so-called «cases of Crimean saboteurs» are a series of criminal cases initiated by Russian intelligence agencies against Ukrainian citizens detained in Crimea.

- In August 2016, Russian law enforcement officers detained Yevgeniy Panov and Andrey Zakhtey. They were first arrested for 15 days on administrative charges of disorderly conduct (Article 20.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences) and both were later taken into custody on charges of preparing to commit sabotage (Part 2 of Article 281 of the Criminal Code with the application of Part 1 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code). Initially, Panov was also charged with participation in an illegal armed formation (Part 2 of Article 208 of the Criminal Code): The FSB claimed that his accomplices who were conducting reconnaissance for subsequent sabotage engaged in a firefight in which a Russian intelligence officer was killed. That charge was later dropped. Panov and Zakhtey were also charged with possession and transportation of weapons (Article 222.3 of the Criminal Code), Panov with attempted smuggling of ammunition (Article 226.1 of the Criminal Code with the application of Article 30.3 of the Criminal Code), Zakhtey with possession and transportation of explosives (Part 3 of Article 222.1 of the Criminal Code), illegal acquisition of a Russian passport (Article 324 of the Criminal Code) and use of a forged document (Part 3 of Article 327 of the Criminal Code). Both reported that they had confessed after torture. Zakhtey was sentenced to six and a half years and Panov to eight years in a strict-regime penal colony. On 7 September 2019, Panov, along with a group of other prisoners, was handed over to Ukraine as part of an exchange. Zakhtey served his sentence and was released in February 2023, following which he was placed in a temporary detention centre for foreign nationals. In June, Zakhtey managed to leave Russia. In 2017, he was stripped of his Russian citizenship.

- Another collective case was initiated against the former officers of the Ukrainian Navy Aleksei Bessarabov, Vladimir Dudka and Dmitry Shtyblikov in Sevastopol in 2016. They were also charged with preparing acts of sabotage on behalf of Ukrainian intelligence and with storing and transporting explosives. In addition, Shtyblikov was charged with storing and transporting weapons. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years in a strict regime penal colony in 2017. Bessarabov and Dudka insisted on their innocence and were sentenced to 14 years in a strict regime penal colony in 2019. Dudka reported being tortured. In August 2020, a new case was initiated against Shtyblikov for treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code) and he was sentenced to 19.5 years in a strict regime penal colony in 2022.

- Several other cases are known where the initial charges involved preparing acts of sabotage and where the charged individuals even recorded confession videos. Some were charged with involvement in the Panov-Zakhtey group and others with ties to the Bessarabov-Dudka-Shtyblikov group. However, later on, neither the sabotage-related charges nor any evidence of involvement in these groups remained in the respective cases (more details can be found in Memorial’s reports).

During this period, persecution of people with pro-Ukrainian views also intensified to a new level.

In 2016, the Crimean activist Vladimir Balukh from the village of Serebryanka was charged with insulting a government official (Article 319 of the Criminal Code) — the complaint against Balukh was filed by a police officer who had previously beaten him. This charge resulted in a sentence of 320 hours of community service, later converted to 40 days in a penal settlement. In November of the same year, Balukh put up a plaque on his property reading «Heavenly Hundred Heroes Street» and in December 2016, the FSB searched his house, claiming they found ammunition. He was charged with illegal possession of weapons and explosives. Despite the lack of clear evidence, Balukh was convicted in 2018 and sentenced to three years and seven months of imprisonment, later reduced by two months on appeal. Russian law enforcement officers did not stop there though: in 2017, when Balukh was already incarcerated, a new criminal case was initiated against him, on charges of assaulting the head of the temporary detention centre (Article 318 of the Criminal Code). This new charge resulted in a five-year prison sentence. In protest, Balukh went on a hunger strike, which he ended after several months due to critical deterioration of his health. In October 2018, the Supreme Court of Crimea reduced his sentence by another month. In 2019, Balukh was released as part of a prisoner exchange between Russia and Ukraine.

Oleh Prykhodko, a Ukrainian activist from Crimea, started facing pressure from Russian authorities in 2016 due to his pro-Ukrainian stance. He was repeatedly summoned by the FSB, fined and charged with distributing prohibited symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences). In October 2019, he was arrested on charges of preparing a terrorist attack (Part 1 of Article 205 with the application of Part 1 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code), as well as acquiring, storing, and manufacturing explosives (Part 1 of Article 222.1 and Part 1 of Article 223.1 of the Criminal Code). Before his arrest, he was held at an FSB facility overnight. His garage was later searched and explosives were allegedly found, which Prykhodko claimed were not his. On 3 March 2021, Prykhodko was sentenced to five years in a strict regime penal colony, with an additional month added in 2022 for contempt of court, a charge stemming from conflicts during his first trial. In 2023, he was sentenced to another four and a half years for rehabilitation of Nazism (Part 1 of Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code) and public calls for terrorism (Part 1 of Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code), though his sentence was reduced by one month in 2024.

Since 2018, Crimea and Sevastopol have also seen widespread use of another common type of criminal prosecution in Russia — initiating cases against Jehovah’s Witnesses. Just like in cases relating to alleged involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir where charges of organising and participating in a terrorist organisation often rely solely on claims of party membership, Jehovah’s Witnesses in Crimea have been prosecuted merely for attending or leading religious services, leading to charges of organising or participating in an extremist organisation (Parts 1 and 2 of Article 282.2 of the Criminal Code). A total of 38 individuals in Crimea have been prosecuted for their alleged ties to communities of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In some cases, individuals charged with association with Jehovah’s Witnesses faced particularly harsh treatment. During a May 2020 series of searches related to cases against Jehovah’s Witnesses in Kerch, law enforcement officers threw Artem Shabliy to the ground, handcuffed him and threatened him with a taser, forcing him to stand next to a shattered window for several hours despite the cold. At the same time, his four-year-old son cut his feet on broken glass. After his interrogation, during which the investigator threatened Shabliy with a long prison term, he was placed in a detention centre without food, water or way of communicating with his family. As Shabiy was leaving the detention centre, he started feeling unwell, but his friends had to take him to the hospital themselves because the ambulance never arrived.

The special approach of Russian authorities to political criminal cases in Crimea is further demonstrated by the practice of prisoner exchanges with Ukraine. From 2016 to 2024, at least ten such exchanges took place. Russia handed over politically prosecuted Ukrainian citizens detained in Crimea in exchange for Russians detained in other parts of Ukraine. These exchanges highlight the military context of Crimea’s illegal occupation and resemble prisoner-of-war swaps (since 2022, they have effectively turned into actual POW exchanges).

In 2017, Turkey played a significant diplomatic role in the release of Crimean Tatar leaders Ilmi Umerov and Akhtem Chiygoz, who had been convicted on politically motivated charges: calls for separatism (Part 2 of Article 280.1 of the Criminal Code) and organising mass riots (Part 1 of Article 212 of the Criminal Code), respectively. The prisoners were pardoned by the Russian president and immediately sent to Turkey. Notably, the pardoned Crimean Tatars held both Ukrainian and Russian citizenship. A somewhat similar instance involving political prisoners in Russia occurred only seven years later — in the summer of 2024, in the third year of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and an unprecedented intensification of domestic repression.

Pressure on Lawyers

Lawyers handling politically motivated cases in Crimea have often themselves faced pressure from Russian authorities. From 2017 to 2023, Crimean Solidarity recorded at least 15 instances of pressure on Crimean human rights lawyers: they were subjected to administrative arrests, stripped of their attorney’s status, and intimidated in order to deter them from defending individuals involved in politically motivated criminal cases.

Administrative arrests are one of the tools used to temporarily neutralise lawyers in Crimea.

For example, in 2017, the police detained the lawyer Emil Kurbedinov on his way to the home of Seiran Saliyev, where a search was being conducted. He was charged under the article on disseminating prohibited symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for a 2013 social media post featuring Hizb ut-Tahrir symbols and was subsequently placed under administrative arrest.

It cannot be ruled out that Russian authorities charged defence lawyers with extremist administrative offences in order to, among other things, create a negative perception of human rights lawyers and marginalise them.

Another way of removing a lawyer from a case was to reclassify the status of the lawyer Nikolai Polozov to a witness in the case of his client Ilmi Umerov, the deputy chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, in 2017.

Lawyers defending Crimean Tatars and others that are prosecuted in occupied Crimea face threats from law enforcement and are subjected to searches.

Prosecutions in Crimea after 2022

Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, prosecutions in Crimea largely continued the trends of previous years, but also took on new characteristics and forms.

OVD-Info recorded the highest number of prosecutions against three key groups: Crimean Tatars (especially activists of Crimean Solidarity), individuals who publicly support Ukraine or condemn Russian aggression and people charged with involvement in sabotage activities.

How has the number of political prosecutions changed in regions controlled by Russia each year since the occupation of Crimea?

Prosecutions of Crimean Tatars

Repressions against the Crimean Tatar population remained one of the main forms of pressure by Russian authorities even after the start of the full-scale war. Most of the criminal cases against Crimean Tatars are related to charges of association with Hizb ut-Tahrir. Since 2022, 38 new prosecutions have been reported for alleged association with Hizb ut-Tahrir (with four prosecutions beginning before the full-scale war).

The persecution of Crimean Solidarity activists who provided support to the prisoners’ families continues. The members of Crimean Solidarity include all of the defendants in the fifth Hizb ut-Tahrir case in Bakhchysarai (Ametkhan Umerov, Seydamet Mustafayev, Ruslan Asanov, Abdulmedzhit Seytumerov, Eldar Yakubov and Remzi Nimetulayev).

In addition, cases relating to involvement with the Noman Chelebidzhikhan Volunteer Battalion continue as well. This group effectively ceased to exist by the end of 2015, but participation in it continues to be used as a formal pretext for repression. Since the start of the full-scale war, at least 10 new prosecutions on this basis have been reported. In all the cases, the actions with which people are charged took place between 2015 and 2019, and in some instances they are based on participation in the 2015 blockade of Crimea or other protest actions that did not involve violence.

Prosecutions of Supporters of Ukraine and Participants in Anti-War Resistance

Shortly after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, criminal cases were initiated against Crimeans charged with spreading «fakes» about the Russian army and discrediting the Russian armed forces. As of March 2025, we are aware of eight prosecutions under Article 280.3 (discrediting the army) and five persecutions under Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code («fakes»).

In addition, Crimea has seen the initiation of at least several dubious cases for the possession of explosives or drugs — people were subjected to searches for their anti-war comments, and the authorities found prohibited substances in their homes during the search.

- For example, the Crimean resident Maksym Lisyuk received a 6-year suspended sentence in such a case, while the Simferopol resident Nikolai Onuk was sentenced to 5 years in a general regime colony for leaflets «with a two-headed eagle pierced by a sword in blue and yellow colours and the words ‘Crimea is Ukraine’», as well as for a suspected TNT detonator found at his home during a search related to suspicions of posting the leaflets.

- During a search related to Daniel Seregin’s anti-war comments, law enforcement officers reportedly found marijuana in his home. He was charged with repeated discrediting of the Russian army (Part 1 of Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code) and illegal possession of drugs (Part 1 of Article 228 of the Criminal Code).

A particularly notable example of prosecution is that of the Crimean nurse and activist Irina Danilovich.

Law enforcement agencies had been pressuring the nurse even before her criminal prosecution: she was detained in 2016 when entering Crimea from mainland Ukraine. In 2017, the woman told Crimea.Realities that FSB officers had tried to coerce her into becoming an informer.

Irina Danilovich disappeared on 29 April 2022. The activist later testified in court that on that day, she was kidnapped by officers of the Crimean FSB. She was held in an FSB basement for about eight days, during which she was tortured and threatened, and likely had explosives planted on her. According to the authorities, the woman was found to be in possession of 200 grams of explosives hidden in the lining of her eyeglass case. She was charged with illegal actions involving explosive substances or devices (Part 1 of Article 222.1 of the Criminal Code). It later turned out that she had been detained on suspicion of treason — allegedly for collecting information about the movement of Russian military equipment in Crimea, but this charge was ultimately not brought against her.

In June 2022, the Russian Ministry of Justice added Danilovich to its register of «foreign agent» media individuals. In December 2022, the Feodosia City Court sentenced the activist to seven years of imprisonment and a fine of 50,000 rubles.

Due to the conditions of her detention in the FSB basement and pre-trial detention, the activist’s health deteriorated significantly. According to human rights defenders, she has nearly lost her hearing and suffers from severe headaches caused by an ear inflammation. In March 2023, after being denied medical care, she went on a hunger strike. In April, she was deceived into ending the hunger strike with promises of hospitalisation, but since then, she has only been examined by a doctor once. In October of the same year, reports emerged that Danilovich may have suffered a stroke in pre-trial detention.

The share of prosecutions in Crimea linked to the war in Ukraine

Following the start of the full-scale invasion, the number of politically motivated criminal cases in Crimea did not rise as sharply as in Russian regions. This may be linked to the fact that Russian law enforcement officers had already initiated numerous political prosecutions there prior to the full-scale invasion. However, immediately after Crimea’s illegal occupation in 2014, political repression primarily targeted Crimean Tatars or opponents of the occupation — both actual and perceived. The number of cases against opponents of the occupation later declined. After the full-scale war began though, the landscape of political prosecutions in Crimea largely came to resemble the Russia-wide pattern.

In particular, after the start of the full-scale invasion, cases began to be initiated in Crimea — as well as in Russia’s territory — over the arson of military recruitment offices and other administrative buildings, or sabotage of railway infrastructure. To extract confessions from the prosecuted individuals, the investigative authorities actively apply pressure, including the use of torture. This was the instance, for example, of 26-year-old Kirill Barannik. On 30 May 2023, he was detained by FSB officers on the embankment in Simferopol. A bag was placed over his head and he was taken in for interrogation during which he confessed to carrying out an act of sabotage in the village of Pochtovoye on 23 February. Barannik stated that the law enforcement officers threatened to kill his mother and tortured him multiple times. According to the young man, at one point they also demanded that he confess to blowing up a railway near the village of Chistenkoye, but he refused to do so.

The number of espionage cases after 2022 is also linked to the fact that, following the breakout of the full-scale war, Crimea became a territory where cases were investigated and considered involving individuals initially detained in other occupied regions. Until the Russian Federation’s law enforcement agencies became fully established in those areas, detainees were transported to Crimea and held there in custody — many of them in extremely harsh conditions. Later, they were either tried in Crimea or transferred to Rostov-on-Don, where the Southern District Military Court is located — a court that handles cases under terrorism-related articles. This is what happened, for example, to Oleksandr Zaryvny, the former head of the Department of Humanitarian Policy of the Kherson District Administration. After the occupation, on 17 March 2022, he was detained by Russian law enforcement officers in Kherson. For the first few weeks, he was held there in a temporary detention facility, and was then transferred to Crimea and charged with espionage. In the autumn of 2023, he was sentenced to 13 years in a strict regime penal colony. His story is similar to those of other Kherson residents — Mykola Petrovsky and Sergey Kotov. Petrovsky was detained on 27 March 2022. He later reported being beaten while held in the military commandant’s office in Kherson. For the next six months, his relatives had no information about his whereabouts. In October 2022, a court-appointed lawyer informed the family that he was being held in Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2 in Simferopol. On 27 September 2023, Petrovsky was sentenced to 16 years in a strict regime penal colony.

Sergey Kotov was detained in April 2022. According to the investigation, he assisted Mykola Petrovsky in providing the Security Service of Ukraine with information about the deployment of Russian troops after the occupation of the city. Kotov was also transferred to Crimea and charged with espionage. On 27 September 2023, he was sentenced to 15 years in a strict regime penal colony.

Administrative Cases

Throughout the entire period of the full-scale invasion, except for the year 2022, the highest number of cases related to the discrediting of the Russian army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) were filed in courts specifically in the occupied territory of Crimea and Sevastopol.

cases under the article on discrediting the Armed Forces in the occupied territories of Crimea and Sevastopol

According to OVD-Info data from 24 February 2022 to 10 March 2025

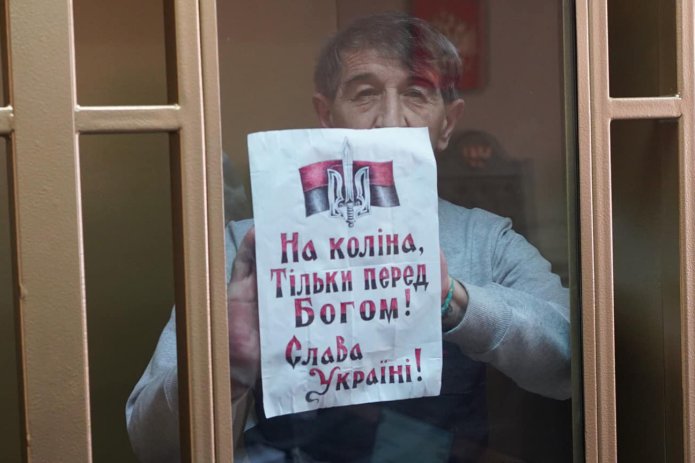

This article was not the only one in the Code of Administrative Offences used to initiate cases in connection with the war. After the start of the full-scale invasion, people began to be prosecuted under the article on displaying extremist symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for various objects and even statements associated with Ukraine — specifically, the symbols of the Azov Regiment, the slogan «Slava Ukraini» and images of the Ukrainian trident.

In 2024, the territory of Crimea accounted for 31% (102 out of 321) of cases related to the display of extremist symbols (Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences) that were initiated for Ukrainian symbols and sent to Russian courts.

Forced Apologies

One of the active enforcers of extrajudicial pressure has been the Telegram channel Crimean SMERSH, which serves as a sort of public registry of «enemies of the people».

Crimean SMERSH began operating in November 2022 and has since become one of the major channels for informing law enforcement authorities. Compared to many similar Telegram resources operating in various Russian-controlled territories (at least 25 Russian regions and three occupied Ukrainian territories), the Crimean channel has a rather impressive audience — over 100,000 followers. The Sevastopol version of the channel, managed by the same Talipov, has around 15,000 followers.

In the early months of its existence, the content of Crimean SMERSH was limited to screenshots of anti-war posts, pro-Ukrainian graffiti and other statements opposing Russian policy. In the posts, law enforcement officers were called upon to «find and punish the perpetrators». The channel later began posting videos of apologies from people who were caught exhibiting insufficient loyalty.

Although the practice of video apologies before the authorities in Russia was initially widespread only in Chechnya, after 2022, similar videos began to be published everywhere. Public apologies are now demanded from individuals with an anti-war stance. This practice is especially popular in Crimea — the occupied peninsula has accounted for more than 88% of such cases since 24 February 2022.

The occupied Crimea has seen the highest number of instances of extrajudicial pressure since the breakout of the war

For example, apologies were demanded from Crimeans for:

- Listening to Ukrainian music in public places,

- Having playlists with Ukrainian songs on VKontakte,

- Removing the Russian flag from car licence plates,

- Using a passport cover with the Ukrainian flag (in one video, a person was forced to burn it),

- Critically speaking about the war in private conversations.

Crimean SMERSH directly interacts with Russian law enforcement agencies. The police detains many of the people whose posts or comments appear on the channel and subjects them to administrative or criminal prosecution. According to Talipov himself, his team «only records the offences», and the rest is done by the state machine. However, the regular publication of photographs of the detainees, their personal data, search footages and even videos of arrests on the channel indicates its close coordination with Russian law enforcement agencies.

Talipov has repeatedly and publicly thanked the Centre E (the Centre for Combating Extremism), the FSB and the police for their prompt arrests. A source in the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Crimea also confirms the connection with law enforcement officers, as reported by Novaya Gazeta.

Forced apologies are just the first stage of pressure on Crimeans. After recording such videos, most individuals are fined under the article on discrediting the army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences), and in some cases, criminal prosecution is initiated. For example, a case was opened against Olga Saenko from Kerch for calls to extremist activity (Article 280 of the Criminal Code). Talipov stated that she started facing charges after his denunciation. Other consequences of being mentioned by name in Crimean SMERSH include either dismissals — this happened to the teacher Medina Bekirova, the nurse Anisiya Yankova and the Simferopol airport employee Natalia — or the loss of an attorney’s status, as was the case with Alexei Ladin.

Other Kinds of Extrajudicial Repression

While criminal repression in occupied Crimea over the past three years of the full-scale war have begun to resemble the repressive practices in Russia, the area of extrajudicial forms of persecution and violence is dominated by other tendences. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the practice of forced disappearances has resumed with new intensity in Crimea. Since 2022, 61 new instances of forced disappearances and one death have been documented. In total, from 2014 to 2024, there have been 104 instances of disappearances of pro-Ukrainian activists, members of Crimean Tatar institutions and journalists (95 men and nine women). As of December 2024, the fate of 21 people remained unknown — they are considered missing. Human rights defenders explain the rise in abductions since the start of the full-scale war against Ukraine by noting that disappearances have become part of the tactic of filtering refugees, including in the occupied territory of Crimea, and, on the other hand, a tool for harsher prosecution for sabotage and guerilla resistance.

Since 2022, the problem of mobilising the local population for the war against Ukraine has intensified in occupied Crimea as well. Military draft conducted in the occupied territories is a violation of international humanitarian law in itself. According to CrimeaSOS calculations, about 90% of draft notices in Crimea were issued to Crimean Tatars, despite the fact that they constitute only a tenth of the total population of the peninsula. This selective attitude towards the Crimean Tatar population can be explained not only by discrimination against the indigenous population, but also by the effort of Russian authorities to use mobilisation as an instrument of pressure towards a disloyal social group.

Conditions of Detention and Practice of Violence

Before 2022, there was only one functioning detention facility in occupied Crimea — Pre-Trial Detention No. 1 in Simferopol. Most politically prosecuted Crimeans passed through it. Constructed in the early 19th century, the building had long since ceased to meet the standards for holding detainees.

With the start of the full-scale war, conditions of detention for political prisoners in Crimea have remained harsh. A significant number of Crimean Tatars serving long sentences are elderly people suffering from chronic illnesses.

Medical care in penal colonies and detention centres often remains inaccessible, while religious discrimination is manifested by bans on Muslim rituals. Muslim Aliyev, a prominent victim of religious discrimination, was placed in a punishment cell for 15 days simply because he refused to interrupt his prayer (Salah) when the prison warden entered his cell.

At the same time, poor detention conditions and discrimination also affect political prisoners from Russia, highlighting deeper systemic issues within the Russian-controlled penitentiary system. Rather than being an exception, the treatment of prosecuted Crimeans reflects a broader disregard for political prisoners as a whole.

Simferopol’s Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2, opened in September 2020, became a key instrument of repression in Crimea. It is primarily used for holding people abducted from the occupied territories. According to Crimean human rights activists, at least 110 people were being held in the new facility at the end of 2022, after being transported there from the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions. Following their abduction, they were subjected to torture that continued even inside the detention centre overseen by the FSB.

The prosecution of many political prisoners has taken a severe toll on their health. Many prosecuted Crimeans are elderly people suffering from chronic illnesses. Yet, FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service) officers often refuse to provide them with necessary medical care. At least two Crimean political prisoners are known to have died in custody.

- In March 2023, the Crimean Tatar activist Jemil Gafarov, who was prosecuted in the second Simferopol case of Hizb ut-Tahrir, died of a heart attack in the pre-trial detention centre in Novocherkassk. Gafarov suffered from kidney failure and a related heart condition.

- On 13 March 2024, after two years of imprisonment under harsh conditions, Rustem Virati, charged with participating in the Crimean Tatar Noman Chelebidzhikhan Volunteer Battalion, died in a penal colony in the city of Dimitrovgrad in the Ulyanovsk region.

Conclusion

The Russian repressive regime not only transferred its previously tested practices to occupied Crimea, but also adapted them to the new context. We have divided the process into three stages:

- The period of transition and the creation of the infrastructure for repression during the first two years of occupation, from 2014 to 2015;

- The functioning of the already established repressive regime from 2016 to 2021;

- The transformation of repression in the context of the full-scale aggression against Ukraine since 2022.

During the first stage, Russian authorities and their affiliated agents combined various repressive practices in Crimea, ranging from abductions to releases from custody under surety. Simultaneously, a foundation was laid for future mass repressions and the suppression of rights and freedoms in Crimea. Specifically, this included the criminalisation of protest and assemblies, closure of independent media outlets, persecution of journalists, forcing out NGOs not controlled by Russian authorities, and the initiation of high-profile terrorism cases. Moreover, some practices, such as declaring the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People an extremist organisation, became a kind of innovation, subsequently applied in Russia as well (e.g. the designation of the FBK [Anti-Corruption Foundation] as an extremist organisation in 2021).

Persecution of Muslims accused of links with Hizb ut-Tahrir, an organisation designated as terrorist in Russia, has become one of the key instruments of repression in Crimea. In the Crimean context, this practice took on a specific nuance, acting as a tool of pressure against activists and independent civil society — predominantly Crimean Tatars. The foundations for this practice were also laid during the «period of transition», with the first criminal case emerging as early as 2015.

In 2016, the number of newly documented politically motivated criminal prosecutions nearly doubled compared to the previous year, reaching 38. This surge may indicate the completion of the establishment of the repressive infrastructure and the beginning of its operation «at full capacity» from 2016 until the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Politically motivated cases from this period include the aforementioned charges of association with Hizb ut-Tahrir, with increasingly frequent instances of such charges being instrumentalised against activists of Crimean Solidarity (an organisation of relatives and defenders of Crimean Tatar victims of repression, formed in 2016). Cases aimed at creating the perception of a military or terrorist threat on the occupied peninsula were also common during this period, such as various charges brought against Crimeans for sabotage and participation in an «illegal armed formation», such as the Crimean Tatar Noman Chelebidzhikhan Battalion. The practice of prosecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses on charges of extremism extended to the peninsula; this practice became increasingly common during this period and essentially differs little from what happens to Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia. Along with the increased number of instances of criminal repression, the visibility and importance of human rights lawyers grew and, consequently, they very quickly became targets of persecution in Crimea themselves.

Amid the full-scale invasion, occupied Crimea has witnessed an unprecedented increase in the number of the new politically motivated criminal cases — as many as 56 in 2022. The increase was driven by cases initiated for anti-war statements under the then-newly introduced articles on military «fakes» and discrediting the Russian army, as well as charges of terrorism and extremism that are already typical for occupied Crimea and other prosecutions related to the war. More than half (6) of all cases of espionage known to us since 2022 were initiated by Russian authorities in Crimea.

Occupied Crimea and Sevastopol lead both in the number of administrative cases concerning the discreditation of the army filed in Russia-controlled courts, as well as in the number of instances of extrajudicial pressure in response to anti-war activities documented by OVD-Info over more than three years of the full-scale war. Crimean SMERSH — an initiative close to law enforcement that maintains its own registry of «enemies of the people» — plays a significant role in the extrajudicial pressure on the peninsula.

The practice of enforced disappearances resumed in occupied Crimea in 2022. In this period, it was linked to the filtration of refugees from the newly occupied territories of eastern Ukraine, as well as to the intensified repression in relation to various forms of resistance in Crimea.

Over 11 years, the Russian occupation of Crimea has shown not only how repression evolves — with the element of the war playing a key role — but also how the regime operates with impunity, just as it does within Russia. This leaves victims of state pressure deprived of any practical access to effective investigations, fair judicial processes, compensation or restoration of their rights.

However, repression does not exist in a vacuum. It can provoke a reaction from the part of society that demonstrates solidarity and the will to resist. An example of this is Crimean Solidarity, which continues to play an important role in monitoring and documenting mass human rights violations on the occupied peninsula, as well as in supporting repressed activists and their families.

Download PDF version

Download PDF version